Monday, November 27. 2023

A Newsletter about Climate Change and Industrial Decarbonization

Noticing that my old blog still gets considerable traffic and has a substantial number of people accessing its feeds, I thought I should announce a project I recently started.

Noticing that my old blog still gets considerable traffic and has a substantial number of people accessing its feeds, I thought I should announce a project I recently started.When discussing climate change and solutions, we often consider actions like replacing coal power plants with clean energy sources. But while these are important, they are the easy part. There is a whole range of emission sources that are much harder to avoid.

Over a decade ago, I covered climate change for a German online publication. Due to the carbon capture and storage debate, I learned that some industrial processes have emissions that cannot be easily avoided. The largest and most well-known examples are steelmaking, where coal chemically reduces iron oxide to iron, and cement production, which uses carbon-containing minerals as an input material.

But while these are the most well-known and emission-wise most significant examples, they are not the only ones.

I eventually found this so interesting that I started my own publication about it in the form of a newsletter. Several things contributed to this: I wanted to discuss topics like these more in-depth and publish more in English, and I saw that multiple other journalists in the field of energy and climate started running their own newsletters, podcasts, or other publications.

If this sounds interesting to you, check the stories I already published. Some topics I have already covered include easily avoidable N₂O emissions in the chemical industry, an overview of CCS, issues with green electricity certificates from Iceland and Norway (another update on that one will come soon), an experimental, fully electrified steelmaking process, and most recently about methanol as an electricity storage technology. And if you find them interesting, please subscribe. If you prefer that, an RSS feed is also available.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Ecology, English, Politics, Science

at

21:09

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Wednesday, March 15. 2017

Zero Days and Cargo Cult Science

I've complained in the past about the lack of rigorous science in large parts of IT security. However there's no lack of reports and publications that claim to provide data about this space.

Recently RAND Corporation, a US-based think tank, published a report about zero day vulnerabilities. Many people praised it, an article on Motherboard quotes people saying that we finally have “cold hard data” and quoting people from the zero day business who came to the conclusion that this report clearly confirms what they already believed.

I read the report. I wasn't very impressed. The data is so weak that I think the conclusions are almost entirely meaningless.

The story that is spun around this report needs some context: There's a market for secret security vulnerabilities, often called zero days or 0days. These are vulnerabilities in IT products that some actors (government entities, criminals or just hackers who privately collect them) don't share with the vendor of that product or the public, so the vendor doesn't know about them and can't provide a fix.

One potential problem of this are bug collisions. Actor A may find or buy a security bug and choose to not disclose it and use it for its own purposes. If actor B finds the same bug then he might use it to attack actor A or attack someone else. If A had disclosed that bug to the vendor of the software it could've been fixed and B couldn't have used it, at least not against people who regularly update their software. Depending on who A and B are (more or less democratic nation states, nation states in conflict with each other or simply criminals) one can argue how problematic that is.

One question that arises here is how common that is. If you found a bug – how likely is it that someone else will find the same bug? The argument goes that if this rate is low then stockpiling vulnerabilities is less problematic. This is how the RAND report is framed. It tries to answer that question and comes to the conclusion that bug collisions are relatively rare. Thus many people now use it to justify that zero day stockpiling isn't so bad.

The data is hardly trustworthy

The basis of the whole report is an analysis of 207 bugs by an entity that shared this data with the authors of the report. It is incredibly vague about that source. They name their source with the hypothetical name BUSBY.

We can learn that it's a company in the zero day business and indirectly we can learn how many people work there on exploit development. Furthermore we learn: “Some BUSBY researchers have worked for nation-states (so

their skill level and methodology rival that of nation-state teams), and many of BUSBY’s products are used by nation-states.” That's about it. To summarize: We don't know where the data came from.

The authors of the study believe that this is a representative data set. But it is not really explained why they believe so. There are numerous problems with this data:

Naturally BUSBY has an interest in a certain outcome and interpretation of that data. This creates a huge conflict of interest. It is entirely possible that they only chose to share that data because they expected a certain outcome. And obviously the reverse is also true: Other companies may have decided not to share such data to avoid a certain outcome. It creates an ideal setup for publication bias, where only the data supporting a certain outcome is shared.

It is inexcusable that the problem of conflict of interest isn't even mentioned or discussed anywhere in the whole report.

A main outcome is based on a very dubious assumption

The report emphasizes two main findings. One is that the lifetime of a vulnerability is roughly seven years. With the caveat that the data is likely biased, this claim can be derived from the data available. It can reasonably be claimed that this lifetime estimate is true for the 207 analyzed bugs.

The second claim is about the bug collision rate and is much more problematic:

“For a given stockpile of zero-day vulnerabilities, after a year, approximately 5.7 percent have been discovered by an outside entity.”

Now think about this for a moment. It is absolutely impossible to know that based on the data available. This would only be possible if they had access to all the zero days discovered by all actors in that space in a certain time frame. It might be possible to extrapolate this if you'd know how many bugs there are in total on the market - but you don't.

So how does this report solve this? Well, let it speak for itself:

Ideally, we would want similar data on Red (i.e., adversaries of Blue, or other private-use groups), to examine the overlap between Blue and Red, but we could not obtain that data. Instead, we focus on the overlap between Blue and the public (i.e., the teal section in the figures above) to infer what might be a baseline for what Red has. We do this based on the assumption that what happens in the public groups is somewhat similar to what happens in other groups. We acknowledge that this is a weak assumption, given that the composition, focus, motivation, and sophistication of the public and private groups can be fairly different, but these are the only data available at this time. (page 12)

Okay, weak assumption may be the understatement of the year. Let's summarize this: They acknowledge that they can't answer the question they want to answer. So they just answer an entirely different question (bug collision rate between the 207 bugs they have data about and what is known in public) and then claim that's about the same. To their credit they recognize that this is a weak assumption, but you have to read the report to learn that. Neither the summary nor the press release nor any of the favorable blog posts and media reports mention that.

If you wonder what the Red and Blue here means, that's also quite interesting, because it gives some insights about the mode of thinking of the authors. Blue stands for the “own team”, a company or government or anyone else who has knowledge of zero day bugs. Red is “the adversary” and then there is the public. This is of course a gross oversimplification. It's like a world where there are two nation states fighting each other and no other actors that have any interest in hacking IT systems. In reality there are multiple Red, Blue and in-between actors, with various adversarial and cooperative relations between them.

Sometimes the best answer is: We don't know

The line of reasoning here is roughly: If we don't have good data to answer a question, we'll just replace it with bad data.

I can fully understand the call for making decisions based on data. That is usually a good thing. However, it may simply be that this is a scenario where getting reliable data is incredibly hard or simply impossible. In such a situation the best thing one can do is admit that and live with it. I don't think it's helpful to rely on data that's so weak that it's basically meaningless.

The core of the problem is that we're talking about an industry that wants to be secret. This secrecy is in a certain sense in direct conflict with good scientific practice. Transparency and data sharing are cornerstones of good science.

I should mention here that shortly afterwards another study was published by Trey Herr and Bruce Schneier which also tries to answer the question of bug collisions. I haven't read it yet, from a brief look it seems less bad than the RAND report. However I have my doubts about it as well. It is only based on public bug findings, which is at least something that has a chance of being verifiable by others. It has the same problem that one can hardly draw conclusions about the non-public space based on that. (My personal tie in to that is that I had a call with Trey Herr a while ago where he asked me about some of my bug findings. I told him my doubts about this.)

The bigger picture: We need better science

IT security isn't a field that's rich of rigorous scientific data.

There's a lively debate right now going on in many fields of science about the integrity of their methods. Psychologists had to learn that many theories they believed for decades were based on bad statistics and poor methodology and are likely false. Whenever someone tries to replicate other studies the replication rates are abysmal. Smart people claim that the majority scientific outcomes are not true.

I don't see this debate happening in computer science. It's certainly not happening in IT security. Almost nobody is doing replications. Meta analyses, trials registrations or registered reports are mostly unheard of.

Instead we have cargo cult science like this RAND report thrown around as “cold hard data” we should rely upon. This is ridiculous.

I obviously have my own thoughts on the zero days debate. But my opinion on the matter here isn't what this is about. What I do think is this: We need good, rigorous science to improve the state of things. We largely don't have that right now. And bad science is a poor replacement for good science.

Recently RAND Corporation, a US-based think tank, published a report about zero day vulnerabilities. Many people praised it, an article on Motherboard quotes people saying that we finally have “cold hard data” and quoting people from the zero day business who came to the conclusion that this report clearly confirms what they already believed.

I read the report. I wasn't very impressed. The data is so weak that I think the conclusions are almost entirely meaningless.

The story that is spun around this report needs some context: There's a market for secret security vulnerabilities, often called zero days or 0days. These are vulnerabilities in IT products that some actors (government entities, criminals or just hackers who privately collect them) don't share with the vendor of that product or the public, so the vendor doesn't know about them and can't provide a fix.

One potential problem of this are bug collisions. Actor A may find or buy a security bug and choose to not disclose it and use it for its own purposes. If actor B finds the same bug then he might use it to attack actor A or attack someone else. If A had disclosed that bug to the vendor of the software it could've been fixed and B couldn't have used it, at least not against people who regularly update their software. Depending on who A and B are (more or less democratic nation states, nation states in conflict with each other or simply criminals) one can argue how problematic that is.

One question that arises here is how common that is. If you found a bug – how likely is it that someone else will find the same bug? The argument goes that if this rate is low then stockpiling vulnerabilities is less problematic. This is how the RAND report is framed. It tries to answer that question and comes to the conclusion that bug collisions are relatively rare. Thus many people now use it to justify that zero day stockpiling isn't so bad.

The data is hardly trustworthy

The basis of the whole report is an analysis of 207 bugs by an entity that shared this data with the authors of the report. It is incredibly vague about that source. They name their source with the hypothetical name BUSBY.

We can learn that it's a company in the zero day business and indirectly we can learn how many people work there on exploit development. Furthermore we learn: “Some BUSBY researchers have worked for nation-states (so

their skill level and methodology rival that of nation-state teams), and many of BUSBY’s products are used by nation-states.” That's about it. To summarize: We don't know where the data came from.

The authors of the study believe that this is a representative data set. But it is not really explained why they believe so. There are numerous problems with this data:

- We don't know in which way this data has been filtered. The report states that 20-30 bugs “were removed due to operational sensitivity”. How was that done? Based on what criteria? They won't tell you. Were the 207 bugs plus the 20-30 bugs all the bugs the company had found or was this already pre-filtered? They won't tell you.

- It is plausible to assume that a certain company focuses on specific bugs, has certain skills, tools or methods that all can affect the selection of bugs and create biases.

- Oh by the way, did you expect to see the data? Like a table of all the bugs analyzed with the at least the little pieces of information BUSBY was willing to share? Because you were promised to see cold hard data? Of course not. That would mean others could reanalyze the data, and that would be unfortunate. The only thing you get are charts and tables summarizing the data.

- We don't know the conditions under which this data was shared. Did BUSBY have any influence on the report? Were they allowed to read it and comment on it before publication? Did they have veto rights to the publication? The report doesn't tell us.

Naturally BUSBY has an interest in a certain outcome and interpretation of that data. This creates a huge conflict of interest. It is entirely possible that they only chose to share that data because they expected a certain outcome. And obviously the reverse is also true: Other companies may have decided not to share such data to avoid a certain outcome. It creates an ideal setup for publication bias, where only the data supporting a certain outcome is shared.

It is inexcusable that the problem of conflict of interest isn't even mentioned or discussed anywhere in the whole report.

A main outcome is based on a very dubious assumption

The report emphasizes two main findings. One is that the lifetime of a vulnerability is roughly seven years. With the caveat that the data is likely biased, this claim can be derived from the data available. It can reasonably be claimed that this lifetime estimate is true for the 207 analyzed bugs.

The second claim is about the bug collision rate and is much more problematic:

“For a given stockpile of zero-day vulnerabilities, after a year, approximately 5.7 percent have been discovered by an outside entity.”

Now think about this for a moment. It is absolutely impossible to know that based on the data available. This would only be possible if they had access to all the zero days discovered by all actors in that space in a certain time frame. It might be possible to extrapolate this if you'd know how many bugs there are in total on the market - but you don't.

So how does this report solve this? Well, let it speak for itself:

Ideally, we would want similar data on Red (i.e., adversaries of Blue, or other private-use groups), to examine the overlap between Blue and Red, but we could not obtain that data. Instead, we focus on the overlap between Blue and the public (i.e., the teal section in the figures above) to infer what might be a baseline for what Red has. We do this based on the assumption that what happens in the public groups is somewhat similar to what happens in other groups. We acknowledge that this is a weak assumption, given that the composition, focus, motivation, and sophistication of the public and private groups can be fairly different, but these are the only data available at this time. (page 12)

Okay, weak assumption may be the understatement of the year. Let's summarize this: They acknowledge that they can't answer the question they want to answer. So they just answer an entirely different question (bug collision rate between the 207 bugs they have data about and what is known in public) and then claim that's about the same. To their credit they recognize that this is a weak assumption, but you have to read the report to learn that. Neither the summary nor the press release nor any of the favorable blog posts and media reports mention that.

If you wonder what the Red and Blue here means, that's also quite interesting, because it gives some insights about the mode of thinking of the authors. Blue stands for the “own team”, a company or government or anyone else who has knowledge of zero day bugs. Red is “the adversary” and then there is the public. This is of course a gross oversimplification. It's like a world where there are two nation states fighting each other and no other actors that have any interest in hacking IT systems. In reality there are multiple Red, Blue and in-between actors, with various adversarial and cooperative relations between them.

Sometimes the best answer is: We don't know

The line of reasoning here is roughly: If we don't have good data to answer a question, we'll just replace it with bad data.

I can fully understand the call for making decisions based on data. That is usually a good thing. However, it may simply be that this is a scenario where getting reliable data is incredibly hard or simply impossible. In such a situation the best thing one can do is admit that and live with it. I don't think it's helpful to rely on data that's so weak that it's basically meaningless.

The core of the problem is that we're talking about an industry that wants to be secret. This secrecy is in a certain sense in direct conflict with good scientific practice. Transparency and data sharing are cornerstones of good science.

I should mention here that shortly afterwards another study was published by Trey Herr and Bruce Schneier which also tries to answer the question of bug collisions. I haven't read it yet, from a brief look it seems less bad than the RAND report. However I have my doubts about it as well. It is only based on public bug findings, which is at least something that has a chance of being verifiable by others. It has the same problem that one can hardly draw conclusions about the non-public space based on that. (My personal tie in to that is that I had a call with Trey Herr a while ago where he asked me about some of my bug findings. I told him my doubts about this.)

The bigger picture: We need better science

IT security isn't a field that's rich of rigorous scientific data.

There's a lively debate right now going on in many fields of science about the integrity of their methods. Psychologists had to learn that many theories they believed for decades were based on bad statistics and poor methodology and are likely false. Whenever someone tries to replicate other studies the replication rates are abysmal. Smart people claim that the majority scientific outcomes are not true.

I don't see this debate happening in computer science. It's certainly not happening in IT security. Almost nobody is doing replications. Meta analyses, trials registrations or registered reports are mostly unheard of.

Instead we have cargo cult science like this RAND report thrown around as “cold hard data” we should rely upon. This is ridiculous.

I obviously have my own thoughts on the zero days debate. But my opinion on the matter here isn't what this is about. What I do think is this: We need good, rigorous science to improve the state of things. We largely don't have that right now. And bad science is a poor replacement for good science.

Wednesday, June 18. 2014

Should science journalists read the studies they write about?

Today I had a little twitter conversation which made me think about the responsibilities a science journalist has. It all started with a quote from Ivan Oransky (who is the editor of Retraction Watch) who said reporting on a study without reading it is 'journalist malpractice'. The source of this is another person who probably just heard him saying that, so I'm not sure what his exact words were.

Admittedly my first thought was: "He is right, too many journalists report about things they don't understand." My second thought was: "If he is right then I am probably guilty of 'journalist malpractice'." So I gave it a second thought and I probably won't agree with the statement any more.

I had a quick look at articles I wrote in the past and I have identified the last ten ones that more or less were coverages of a scientific piece of work. I have marked the ones I actually read with a [Y] and the ones I didn't read with a [N]. I've linked the appropriate scientific works and my articles (all in German). I must admit that I defined "read" widely, meaning that I haven't neccesarrily read the whole study/article in detail, I sometimes have just tried to parse the important parts for me.

Now the first thing that comes to mind is that I seem to have become lazier recently in reading studies. I hope this isn't the case and I hoestly think this is mostly coincidence. Now let's get into some details: The first example (the Turing Test) is interesting because it seems there is no scientific publication at all, just a press release. This probably tells you something about the quality of that "research", but while I read the press release I haven't even bothered to check if there is a scientific publication I could read.

The second example becomes interesting. I understand enough to know what a "quasi-polynomial algorithm for discrete logarithm in finite fields of small characteristic" actually is and I think I also understand what it means, but there's just no way I could understand the paper itself. This is complex mathematics. I seriously doubt that any journalist who covered this work actually read it. If there is I'd like to meet that person. I'm also very sure that the people who wrote the press release overselling this research have neither read this paper nor understood its implications.

I think this example gets to the point why I would disagree with the very general statement that a journalist should've read every scientific piece he writes about: It's sometimes so specialized that it's basically impossible. And I don't think this is an out of the line example. Just think about the Higgs Boson: Certainly this is something we want journalists to write about. But I'm pretty sure there are very few - if any - journalists who are able to read the scientific publications that are the basis of this discovery.

Some quick notes on the others: Number 4 was part of a 200-page-thesis and the press release was already pretty detailed and technically, I think it was legitimate to not read the original source in that case. Number 5 is somewhat similar to 2, because it is about an algorithm that includes complex math. Number 8 is not really a scientific paper, it is merely a news item on the Nature webpage. In the above list, the only case where I think maybe I should've read the scientific paper and I didn't is the Cochrane-Review on Tamiflu.

Conclusion: Don't get me wrong. I certainly welcome the idea that science journalists should have a look into the original scientific papers they write about more often - and this doesn't exclude myself. However, as shown above I doubt that this works in all cases.

Admittedly my first thought was: "He is right, too many journalists report about things they don't understand." My second thought was: "If he is right then I am probably guilty of 'journalist malpractice'." So I gave it a second thought and I probably won't agree with the statement any more.

I had a quick look at articles I wrote in the past and I have identified the last ten ones that more or less were coverages of a scientific piece of work. I have marked the ones I actually read with a [Y] and the ones I didn't read with a [N]. I've linked the appropriate scientific works and my articles (all in German). I must admit that I defined "read" widely, meaning that I haven't neccesarrily read the whole study/article in detail, I sometimes have just tried to parse the important parts for me.

- [X] Supposedly successful Turing Test taz, 2014-06-13

- [N]A quasi-polynomial algorithm for discrete logarithm in finite fields of small characteristic, Golem.de, 2014-05-17

- [N] Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children (Cochrane-Review on Tamiflu), Neues Deutschland, 2014-04-26)

- [N] 20 Years of SSL/TLS Research: An Analysis of the Internet's Security Foundation, Golem.de, 2014-04-17

- [N] DRAFT FIPS 202 - SHA-3 Standard: Permutation-Based Hash and Extendable-Output Functions, Golem, 2014-04-05

- [Y] Using Frankencerts for Automated Adversarial Testing of Certificate Validation in SSL/TLS Implementations, Golem.de, 2014-04-04

- [Y] On the Practical Exploitability of Dual EC in TLS Implementations, Golem.de, 2014-04-01

- [Y] Publishers withdraw more than 120 gibberish papers, Golem.de, 2014-02-27

- [Y] Completeness of Reporting of Patient-Relevant Clinical Trial Outcomes: Comparison of Unpublished Clinical Study Reports with Publicly Available Data, taz, 2013-10-18

- [Y] Factoring RSA keys from certified smart cards: Coppersmith in the wild, Golem.de, 2013-09-17

Now the first thing that comes to mind is that I seem to have become lazier recently in reading studies. I hope this isn't the case and I hoestly think this is mostly coincidence. Now let's get into some details: The first example (the Turing Test) is interesting because it seems there is no scientific publication at all, just a press release. This probably tells you something about the quality of that "research", but while I read the press release I haven't even bothered to check if there is a scientific publication I could read.

The second example becomes interesting. I understand enough to know what a "quasi-polynomial algorithm for discrete logarithm in finite fields of small characteristic" actually is and I think I also understand what it means, but there's just no way I could understand the paper itself. This is complex mathematics. I seriously doubt that any journalist who covered this work actually read it. If there is I'd like to meet that person. I'm also very sure that the people who wrote the press release overselling this research have neither read this paper nor understood its implications.

I think this example gets to the point why I would disagree with the very general statement that a journalist should've read every scientific piece he writes about: It's sometimes so specialized that it's basically impossible. And I don't think this is an out of the line example. Just think about the Higgs Boson: Certainly this is something we want journalists to write about. But I'm pretty sure there are very few - if any - journalists who are able to read the scientific publications that are the basis of this discovery.

Some quick notes on the others: Number 4 was part of a 200-page-thesis and the press release was already pretty detailed and technically, I think it was legitimate to not read the original source in that case. Number 5 is somewhat similar to 2, because it is about an algorithm that includes complex math. Number 8 is not really a scientific paper, it is merely a news item on the Nature webpage. In the above list, the only case where I think maybe I should've read the scientific paper and I didn't is the Cochrane-Review on Tamiflu.

Conclusion: Don't get me wrong. I certainly welcome the idea that science journalists should have a look into the original scientific papers they write about more often - and this doesn't exclude myself. However, as shown above I doubt that this works in all cases.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Cryptography, English, Science

at

15:03

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: journalism, science

Saturday, January 26. 2013

Explain hard stuff with the 1000 most common words #UPGOERFIVE

Based on the XKCD comic "Up Goer Five", someone made a nice little tool: An online text editor that lets you only use the 1000 most common words in English. And ask you to explain a hard idea with it.

Nice idea. I gave it a try. The most obvious example to use was my diploma thesis (on RSA-PSS and provable security), where I always had a hard time to explain to anyone what it was all about.

Well, obviously math, proof, algorithm, encryption etc. all are forbidden, but I had a hard time with the fact that even words like "message" (or anything equivalent) don't seem to be in the top 1000.

Here we go:

When you talk to a friend, she or he knows you are the person in question. But when you do this a friend far away through computers, you can not be sure.

That's why computers have ways to let you know if the person you are talking to is really the right person.

The ways we use today have one problem: We are not sure that they work. It may be that a bad person knows a way to be able to tell you that he is in fact your friend. We do not think that there are such ways for bad persons, but we are not completely sure.

This is why some people try to find ways that are better. Where we can be sure that no bad person is able to tell you that he is your friend. With the known ways today this is not completely possible. But it is possible in parts.

I have looked at those better ways. And I have worked on bringing these better ways to your computer.

So - do you now have an idea what I was taking about?

I found this nice tool through Ben Goldacre, who tried to explain randomized trials, blinding, systematic review and publication bias - go there and read it. Knowing what publication bias and systematic reviews are is much more important for you than knowing what RSA-PSS is. You can leave cryptography to the experts, but you should care about your health. And for the record, I recently tried myself to explain publication bias (german only).

Nice idea. I gave it a try. The most obvious example to use was my diploma thesis (on RSA-PSS and provable security), where I always had a hard time to explain to anyone what it was all about.

Well, obviously math, proof, algorithm, encryption etc. all are forbidden, but I had a hard time with the fact that even words like "message" (or anything equivalent) don't seem to be in the top 1000.

Here we go:

When you talk to a friend, she or he knows you are the person in question. But when you do this a friend far away through computers, you can not be sure.

That's why computers have ways to let you know if the person you are talking to is really the right person.

The ways we use today have one problem: We are not sure that they work. It may be that a bad person knows a way to be able to tell you that he is in fact your friend. We do not think that there are such ways for bad persons, but we are not completely sure.

This is why some people try to find ways that are better. Where we can be sure that no bad person is able to tell you that he is your friend. With the known ways today this is not completely possible. But it is possible in parts.

I have looked at those better ways. And I have worked on bringing these better ways to your computer.

So - do you now have an idea what I was taking about?

I found this nice tool through Ben Goldacre, who tried to explain randomized trials, blinding, systematic review and publication bias - go there and read it. Knowing what publication bias and systematic reviews are is much more important for you than knowing what RSA-PSS is. You can leave cryptography to the experts, but you should care about your health. And for the record, I recently tried myself to explain publication bias (german only).

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Cryptography, English, Life, Science, Security

at

11:51

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Saturday, October 6. 2012

mycare.de und die Zaubermedizin

Folgende Nachricht habe ich heute an die Onlineapotheke mycare.de geschrieben.

Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren,

Lassen Sie mich kurz etwas vorwegnehmen: Ich habe bereits einige Male bei mycare.de bestellt. Die Preise sind meist günstig und die Lieferungen erfolgten ohne Probleme. Ich teile auch nicht die kulturpessimistische Sorge mancher Zeitgenossen, die Onlineapotheken für schädlich oder gar für den Untergang des Abendlandes halten.

Meiner letzten bei Ihnen bestellten Lieferung lag eine Ausgabe des Magazins “Gesund durch Homöopathie”, herausgegeben von der Deutschen Homöopathie-Union (DHU), bei.

Homöopathie ist keine Medizin – es ist ein Glaubenssystem, das nicht auf wissenschaftlichen Fakten beruht. Homöopathische “Medikamente” bestehen aus Substanzen, die meist so hoch verdünnt sind, dass kein Molekül der Ursprungssubstanz mehr vorhanden ist. Nach den Ideen von Samuel Hahnemann, dem Erfinder der Homöopathie, führt die Verdünnung zu einer Verstärkung des Effekts.

Würde dies tatsächlich stimmen, müssten wir wohl große Teile der Biologie- und auch der Physikbücher umschreiben. So ist es kaum zu erklären, wie sich die Idee der potenzierten Information in Wasserlösungen mit so grundlegenden Dingen wie dem zweiten Hauptsatz der Thermodynamik in Einklang bringen lässt.

Aber – niemand muss die Physikbücher umschreiben, denn alles spricht dafür, dass es sich bei Homöopathie um Pseudomedizin handelt. Zahlreiche Metaanalysen kamen immer wieder zu dem selben Schluss: Bei homöopathischen Medikamenten wirkt lediglich der Placebo-Effekt.

Neben der Tatsache, dass es bei Homöopathie um Zaubermedizin geht, weise ich noch auf folgendes hin: Der Herausgeber der von ihnen verbreiteten Zeitschrift, die Deutschen Homöopathieunion, hatte erst kürzlich einen handfesten Skandal vorzuweisen. Sie finanzierte einen selbsternannten Journalisten, dessen Aufgabe darin bestand, Kritiker der Homöopathie anzuschwärzen. Die Details sind in einem Artikel der Süddeutschen Zeitung beschrieben, auf den ich hier gerne verweise [1].

Aber eigentlich brauche ich Ihnen das nicht zu erzählen. Denn ich gehe davon aus, dass auch bei einer Onlineapotheke Mitarbeiter mit medizinischem Sachverstand angestellt sind. Insofern wissen sie das alles längst, vermutlich besser als ich, der ich lediglich die Kompetenz eines Laien mit Interesse für Wissenschaft vorweisen kann.

Ich weiß nicht, was sie dazu motiviert, derart unwissenschaftliche Propaganda von einer Firma mit fragwürdigen Methoden zu verbreiten. Möglicherweise bekommen sie von der Deutschen Homöopathie-Union dafür Geld, möglicherweise denken sie, dass ihre Kunden derartige “Beigaben” schätzen. Ich halte es für schlicht unverantwortlich. Sie tragen dazu bei, dass unwissenschaftliches Denken gefördert wird. Als Apotheke – auch als Onlineapotheke – haben sie eine Verantwortung. Dazu gehört auch, Patienten keine unsachlichen oder falschen Informationen an die Hand zu geben. Ich werde mir gut überlegen, ob ich in Zukunft noch bei Ihnen einkaufen werde.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen,

Hanno Böck

P.S.: Diese Mail werde ich auf meinem privaten Blog veröffentlichen. Sollten Sie mir hierauf antworten (was ich begrüßen würde), werde ich die Antwort dort ebenfalls veröffentlichen.

[1] http://www.sueddeutsche.de/wissen/homoeopathie-lobby-im-netz-schmutzige-methoden-der-sanften-medizin-1.1397617

In der Hoffnung, dass ich nicht der einzige bin und irgendwann Apotheken damit aufhören, Hokuspokus als Medizin zu verkaufen.

Update: mycare.de hat geantwortet:

Homöopathie ist eine in Deutschland anerkannte alternativmedizinische Behandlungsmethode. So haben Arzt und Patient die Möglichkeit, neben der klassischen Medizin auch die der Homöopathie zu wählen. Viele Kunden von mycare zeigen aufgrund ihrer Bestellungen Interesse an der Homöopathie. Wir möchten dem Wunsch unserer Kunden gerecht werden und informieren daher regelmäßig mit unterschiedlichen Beilagen zu diesem Thema. Eine Beilagensperre können wir für Ihr Konto selbstverständlich einrichten, sofern Sie das wünschen.

Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren,

Lassen Sie mich kurz etwas vorwegnehmen: Ich habe bereits einige Male bei mycare.de bestellt. Die Preise sind meist günstig und die Lieferungen erfolgten ohne Probleme. Ich teile auch nicht die kulturpessimistische Sorge mancher Zeitgenossen, die Onlineapotheken für schädlich oder gar für den Untergang des Abendlandes halten.

Meiner letzten bei Ihnen bestellten Lieferung lag eine Ausgabe des Magazins “Gesund durch Homöopathie”, herausgegeben von der Deutschen Homöopathie-Union (DHU), bei.

Homöopathie ist keine Medizin – es ist ein Glaubenssystem, das nicht auf wissenschaftlichen Fakten beruht. Homöopathische “Medikamente” bestehen aus Substanzen, die meist so hoch verdünnt sind, dass kein Molekül der Ursprungssubstanz mehr vorhanden ist. Nach den Ideen von Samuel Hahnemann, dem Erfinder der Homöopathie, führt die Verdünnung zu einer Verstärkung des Effekts.

Würde dies tatsächlich stimmen, müssten wir wohl große Teile der Biologie- und auch der Physikbücher umschreiben. So ist es kaum zu erklären, wie sich die Idee der potenzierten Information in Wasserlösungen mit so grundlegenden Dingen wie dem zweiten Hauptsatz der Thermodynamik in Einklang bringen lässt.

Aber – niemand muss die Physikbücher umschreiben, denn alles spricht dafür, dass es sich bei Homöopathie um Pseudomedizin handelt. Zahlreiche Metaanalysen kamen immer wieder zu dem selben Schluss: Bei homöopathischen Medikamenten wirkt lediglich der Placebo-Effekt.

Neben der Tatsache, dass es bei Homöopathie um Zaubermedizin geht, weise ich noch auf folgendes hin: Der Herausgeber der von ihnen verbreiteten Zeitschrift, die Deutschen Homöopathieunion, hatte erst kürzlich einen handfesten Skandal vorzuweisen. Sie finanzierte einen selbsternannten Journalisten, dessen Aufgabe darin bestand, Kritiker der Homöopathie anzuschwärzen. Die Details sind in einem Artikel der Süddeutschen Zeitung beschrieben, auf den ich hier gerne verweise [1].

Aber eigentlich brauche ich Ihnen das nicht zu erzählen. Denn ich gehe davon aus, dass auch bei einer Onlineapotheke Mitarbeiter mit medizinischem Sachverstand angestellt sind. Insofern wissen sie das alles längst, vermutlich besser als ich, der ich lediglich die Kompetenz eines Laien mit Interesse für Wissenschaft vorweisen kann.

Ich weiß nicht, was sie dazu motiviert, derart unwissenschaftliche Propaganda von einer Firma mit fragwürdigen Methoden zu verbreiten. Möglicherweise bekommen sie von der Deutschen Homöopathie-Union dafür Geld, möglicherweise denken sie, dass ihre Kunden derartige “Beigaben” schätzen. Ich halte es für schlicht unverantwortlich. Sie tragen dazu bei, dass unwissenschaftliches Denken gefördert wird. Als Apotheke – auch als Onlineapotheke – haben sie eine Verantwortung. Dazu gehört auch, Patienten keine unsachlichen oder falschen Informationen an die Hand zu geben. Ich werde mir gut überlegen, ob ich in Zukunft noch bei Ihnen einkaufen werde.

Mit freundlichen Grüßen,

Hanno Böck

P.S.: Diese Mail werde ich auf meinem privaten Blog veröffentlichen. Sollten Sie mir hierauf antworten (was ich begrüßen würde), werde ich die Antwort dort ebenfalls veröffentlichen.

[1] http://www.sueddeutsche.de/wissen/homoeopathie-lobby-im-netz-schmutzige-methoden-der-sanften-medizin-1.1397617

In der Hoffnung, dass ich nicht der einzige bin und irgendwann Apotheken damit aufhören, Hokuspokus als Medizin zu verkaufen.

Update: mycare.de hat geantwortet:

Homöopathie ist eine in Deutschland anerkannte alternativmedizinische Behandlungsmethode. So haben Arzt und Patient die Möglichkeit, neben der klassischen Medizin auch die der Homöopathie zu wählen. Viele Kunden von mycare zeigen aufgrund ihrer Bestellungen Interesse an der Homöopathie. Wir möchten dem Wunsch unserer Kunden gerecht werden und informieren daher regelmäßig mit unterschiedlichen Beilagen zu diesem Thema. Eine Beilagensperre können wir für Ihr Konto selbstverständlich einrichten, sofern Sie das wünschen.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Life, Science

at

19:20

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: apotheke, dhu, esoterik, homeopathy, homöopathie, medizin, mycare, skeptiker, wissenschaft

Thursday, October 27. 2011

Verteidigung meiner Diplomarbeit

Die Verteidigung meiner Diplomarbeit über RSA-PSS an der HU Berlin wird am 10. November stattfinden. Die Veranstaltung ist öffentlich (17:00 Uhr s. t., Rudower Chausee 25, Campus Berlin-Adlershof, Raum 3'113). Achtung: Termin und Ort verschoben.

Die Verteidigung meiner Diplomarbeit über RSA-PSS an der HU Berlin wird am 10. November stattfinden. Die Veranstaltung ist öffentlich (17:00 Uhr s. t., Rudower Chausee 25, Campus Berlin-Adlershof, Raum 3'113). Achtung: Termin und Ort verschoben.Hier die Ankündigung:

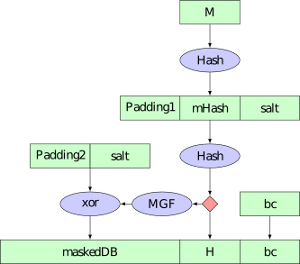

Das Verschlüsselungs- und Signaturverfahren RSA ist das mit Abstand am häufigsten eingesetzte Public Key-Verfahren. RSA kann nicht in seiner ursprünglichen Form eingesetzt werden, da hierbei massive Sicherheitsprobleme auftreten. Zur Vorverarbeitung ist ein sogenanntes Padding notwendig. Bislang wird hierfür meist eine simple Hash-Funktion eingesetzt. Schon 1996 stellten Mihir Bellare und Philipp Rogaway für Signaturen ein verbessertes Verfahren mit dem Namen "Probabilistic Signature Scheme" (PSS) vor. Es garantiert unter bestimmten Annahmen "beweisbare" Sicherheit.

In der Diplomarbeit wurde untersucht, welche Vorteile RSA-PSS gegenüber früheren Verfahren bietet und inwieweit RSA-PSS in verbreiteten Protokollen bereits zum Einsatz kommt. Weiterhin wurde eine Implementierung des Verfahrens für X.509-Zertifikate für die nss-Bibliothek erstellt. nss wird unter anderem von Mozilla Firefox und Google Chrome eingesetzt.

Tuesday, March 1. 2011

Guttenberg: Wie konnte es eigentlich dazu kommen?

Mich juckt es gerade in den Fingern, etwas zum Fall Guttenberg loszuwerden.

Was ich mich ja gerade die ganze Zeit frage: Warum wird eigentlich seine Uni und sein Doktorvater von der Kritik weitgehend verschont? Sein Doktorvater Peter Häberle hat sich ja inzwischen dazu bequemt, sich auch mal zu dem Fall zu äußern und Guttenberg nicht weiter in Schutz zu nehmen.

Ich meine: Wie glaubwürdig ist das denn eigentlich, dass ein Doktorvater in sieben Jahren nicht bemerkt, dass sich sein Schützling offensichtlich gar nicht selbst mit dem Thema beschäftigt? Ich gehe ja naiverweise davon aus, dass in so einem Fall regelmäßige Gespräche stattfinden, in denen man sich über das Thema unterhält und diese Gedanken fließen dann später in die Dissertation ein (zumindest läuft das so bei meiner Diplomarbeit, vielleicht mache ich ja was falsch).

Ich sehe eigentlich nur zwei realistische Erklärungen: Entweder war der Doktorvater direkt am Betrug beteiligt (halte ich für unwahrscheinlich), oder eine ernsthafte Betreuung hat schlicht nicht stattgefunden und er hat nur seinen Namen dafür hergegeben. Und das ist denke ich der zweite Skandal hier, der bislang zu wenig Beachtung gefunden hat.

(dass man eigentlich auch zumindest einen rudimentären Plagiatscheck erwarten sollte, kommt natürlich dazu, aber gut, die Bedienung von Google kann man vermutlich von einem Professor nicht erwarten)

Eine weitere Anmerkung kann ich mir nicht verkneifen: Die FAZ hat die Tage einen Ghostwriter interviewt. "Die meisten Kundenwünsche kommen sowieso aus der Betriebswirtschaft oder dem juristischen Bereich" heißt es dort - ich sags mal so, das überrascht mich jetzt nicht.

Was ich mich ja gerade die ganze Zeit frage: Warum wird eigentlich seine Uni und sein Doktorvater von der Kritik weitgehend verschont? Sein Doktorvater Peter Häberle hat sich ja inzwischen dazu bequemt, sich auch mal zu dem Fall zu äußern und Guttenberg nicht weiter in Schutz zu nehmen.

Ich meine: Wie glaubwürdig ist das denn eigentlich, dass ein Doktorvater in sieben Jahren nicht bemerkt, dass sich sein Schützling offensichtlich gar nicht selbst mit dem Thema beschäftigt? Ich gehe ja naiverweise davon aus, dass in so einem Fall regelmäßige Gespräche stattfinden, in denen man sich über das Thema unterhält und diese Gedanken fließen dann später in die Dissertation ein (zumindest läuft das so bei meiner Diplomarbeit, vielleicht mache ich ja was falsch).

Ich sehe eigentlich nur zwei realistische Erklärungen: Entweder war der Doktorvater direkt am Betrug beteiligt (halte ich für unwahrscheinlich), oder eine ernsthafte Betreuung hat schlicht nicht stattgefunden und er hat nur seinen Namen dafür hergegeben. Und das ist denke ich der zweite Skandal hier, der bislang zu wenig Beachtung gefunden hat.

(dass man eigentlich auch zumindest einen rudimentären Plagiatscheck erwarten sollte, kommt natürlich dazu, aber gut, die Bedienung von Google kann man vermutlich von einem Professor nicht erwarten)

Eine weitere Anmerkung kann ich mir nicht verkneifen: Die FAZ hat die Tage einen Ghostwriter interviewt. "Die meisten Kundenwünsche kommen sowieso aus der Betriebswirtschaft oder dem juristischen Bereich" heißt es dort - ich sags mal so, das überrascht mich jetzt nicht.

Saturday, February 26. 2011

Playing with the EFF SSL Observatory

The Electronic Frontier Foundation is running a fascinating project called the SSL Observatory. What they basically do is quite simple: They collected all SSL certificates they could get via https (by scanning all possible IPs), put them in a database and made statistics with them.

For an introduction, watch their talk at the 27C3 - it's worth it. For example, they found a couple of "Extended Validation"-Certificates that clearly violated the rules for extended validation, including one 512-bit EV-certificate.

The great thing is: They provide the full mysql database for download. I took the time to import the thing locally and am now able to run my own queries against it.

Let's show some examples: I'm interested in crypto algorithms used in the wild, so I wanted to know which are used in the wild at all. My query:

And the result:

This query was only for the valid certs, meaning they were signed by any browser-supported certificate authority. Now I run the same query on the all_certs table, which contains every cert, including expired, self-signed or otherwise invalid ones:

For an introduction, watch their talk at the 27C3 - it's worth it. For example, they found a couple of "Extended Validation"-Certificates that clearly violated the rules for extended validation, including one 512-bit EV-certificate.

The great thing is: They provide the full mysql database for download. I took the time to import the thing locally and am now able to run my own queries against it.

Let's show some examples: I'm interested in crypto algorithms used in the wild, so I wanted to know which are used in the wild at all. My query:

SELECT `Signature Algorithm`, count(*) FROM valid_certs GROUP BY `Signature Algorithm` ORDER BY count(*);shows all signature algorithms used on the certificates.

And the result:

+--------------------------+----------+Nothing very surprising here. Seems nobody is using anything else than RSA. The most popular hash algorithm is SHA-1, followed by MD5. The transition to SHA-256 seems to go very slowly (btw., the most common argument I heared when asking CAs for SHA-256 certificates was that Windows XP before service pack 3 doesn't support that). The four MD2-certificates seem interesting, though even that old, it's still more secure than MD5 and provides a similar security margin as SHA-1, though support for it has been removed from a couple of security libraries some time ago.

| Signature Algorithm | count(*) |

+--------------------------+----------+

| sha512WithRSAEncryption | 1 |

| sha1WithRSA | 1 |

| md2WithRSAEncryption | 4 |

| sha256WithRSAEncryption | 62 |

| md5WithRSAEncryption | 29958 |

| sha1WithRSAEncryption | 1503333 |

+--------------------------+----------+

This query was only for the valid certs, meaning they were signed by any browser-supported certificate authority. Now I run the same query on the all_certs table, which contains every cert, including expired, self-signed or otherwise invalid ones:

+-------------------------------------------------------+----------+It seems quite some people are experimenting with DSA signatures. Interesting are the number of GOST-certificates. GOST was a set of cryptography standards by the former soviet union. Seems the number of people trying to use elliptic curves is really low (compared to the popularity they have and that if anyone cares for SSL performance, they may be a good catch). For the algorithms only showing numbers, 1.2.840.113549.1.1.10 is RSASSA-PSS (not detected by current openssl release versions), 1.3.6.1.4.1.5849.1.3.2 is also a GOST-variant (GOST3411withECGOST3410) and 1.2.840.113549.27.1.5 is unknown to google, so it must be something very special.

| Signature Algorithm | count(*) |

+-------------------------------------------------------+----------+

| 1.2.840.113549.27.1.5 | 1 |

| sha1 | 1 |

| dsaEncryption | 1 |

| 1.3.6.1.4.1.5849.1.3.2 | 1 |

| md5WithRSAEncryption ANDALSO md5WithRSAEncryption | 1 |

| ecdsa-with-Specified | 1 |

| dsaWithSHA1-old | 2 |

| itu-t ANDALSO itu-t | 2 |

| dsaWithSHA | 3 |

| 1.2.840.113549.1.1.10 | 4 |

| ecdsa-with-SHA384 | 5 |

| ecdsa-with-SHA512 | 5 |

| ripemd160WithRSA | 9 |

| md4WithRSAEncryption | 15 |

| sha384WithRSAEncryption | 24 |

| GOST R 34.11-94 with GOST R 34.10-94 | 25 |

| shaWithRSAEncryption | 50 |

| sha1WithRSAEncryption ANDALSO sha1WithRSAEncryption | 72 |

| rsaEncryption | 86 |

| md2WithRSAEncryption | 120 |

| GOST R 34.11-94 with GOST R 34.10-2001 | 378 |

| sha512WithRSAEncryption | 513 |

| sha256WithRSAEncryption | 2542 |

| dsaWithSHA1 | 2703 |

| sha1WithRSA | 60969 |

| md5WithRSAEncryption | 1354658 |

| sha1WithRSAEncryption | 4196367 |

+-------------------------------------------------------+----------+

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Computer culture, Cryptography, English, Science, Security

at

22:40

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: algorithm, certificate, cryptography, eff, observatory, pss, rsa, security, ssl

Tuesday, August 10. 2010

P != NP and what this may mean to cryptography

Yesterday I read via twitter that the HP researcher Vinay Deolalikar claimed to have proofen P!=NP. If you never heared about it, the question whether P=PN or not is probably the biggest unsolved problem in computer science and one of the biggest ones in mathematics. It's one of the seven millenium problems that the Clay Mathematics Institute announced in 2000. Only one of them has been solved yet (Poincaré conjecture) and everyone who solves one gets one million dollar for it.

The P/NP-problem is one of the candidates where many have thought that it may never be solved at all and if this result is true, it's a serious sensation. Obviously, that someone claimed to have solved it does not mean that it is solved. Dozends of pages with complex math need to be peer reviewed by other researchers. Even if it's correct, it will take some time until it'll be widely accepted. I'm far away from understanding the math used there, so I cannot comment on it, but it seems Vinay Deolalikar is a serious researcher and has published in the area before, so it's at least promising. As I'm currently working on "provable" cryptography and this has quite some relation to it, I'll try to explain it a bit in simple words and will give some outlook what this may mean for the security of your bank accounts and encrypted emails in the future.

P and NP are problem classes that say how hard it is to solve a problem. Generally speaking, P problems are ones that can be solved rather fast - more exactly, their running time can be expressed as a polynom. NP problems on the other hand are problems where a simple method exists to verify if they are correct but it's still hard to solve them. To give a real-world example: If you have a number of objects and want to put them into a box. Though you don't know if they fit into the box. There's a vast number of possibilitys how to order the objects so they fit into the box, so it may be really hard to find out if it's possible at all. But if you have a solution (all objects are in the box), you can close the lit and easily see that the solution works (I'm not entirely sure on that but I think this is a variant of KNAPSACK). There's another important class of problems and that are NP complete problems. Those are like the "kings" of NP problems, their meaning is that if you have an efficient algorithm for one NP complete problem, you would be able to use that to solve all other NP problems.

NP problems are the basis of cryptography. The most popular public key algorithm, RSA, is based on the factoring problem. Factoring means that you divide a non-prime into a number of primes, for example factoring 6 results in 2*3. It is hard to do factoring on a large number, but if you have two factors, it's easy to check that they are indeed factors of the large number by multiplying them. One big problem with RSA (and pretty much all other cryptographic methods) is that it's possible that a trick exists that nobody has found yet which makes it easy to factorize a large number. Such a trick would undermine the basis of most cryptography used in the internet today, for example https/ssl.

What one would want to see is cryptography that is provable secure. This would mean that one can proove that it's really hard (where "really hard" could be something like "this is not possible with normal computers using the amount of mass in the earth in the lifetime of a human") to break it. With todays math, such proofs are nearly impossible. In math terms, this would be a lower bound for the complexity of a problem.

And that's where the P!=NP proof get's interesting. If it's true that P!=NP then this would mean NP problems are definitely more complex than P problems. So this might be the first breakthrough in defining lower bounds of complexity. I said above that I'm currently working on "proovable" security (with the example of RSA-PSS), but provable in this context means that you have core algorithms that you believe are secure and design your provable cryptographic system around it. Knowing that P!=NP could be the first step in having really "provable secure" algorithms at the heart of cryptography.

I want to stress that it's only a "first step". Up until today, nobody was able to design a useful public key cryptography system around an NP hard problem. Factoring is NP, but (at least as far as we know) it's not NP hard. I haven't covered the whole topic of quantum computers at all, which opens up a whole lot of other questions (for the curious, it's unknown if NP hard problems can be solved with quantum computers).

As a final conclusion, if the upper result is true, this will lead to a whole new aera of cryptographic research - and some of it will very likely end up in your webbrowser within some years.

The P/NP-problem is one of the candidates where many have thought that it may never be solved at all and if this result is true, it's a serious sensation. Obviously, that someone claimed to have solved it does not mean that it is solved. Dozends of pages with complex math need to be peer reviewed by other researchers. Even if it's correct, it will take some time until it'll be widely accepted. I'm far away from understanding the math used there, so I cannot comment on it, but it seems Vinay Deolalikar is a serious researcher and has published in the area before, so it's at least promising. As I'm currently working on "provable" cryptography and this has quite some relation to it, I'll try to explain it a bit in simple words and will give some outlook what this may mean for the security of your bank accounts and encrypted emails in the future.

P and NP are problem classes that say how hard it is to solve a problem. Generally speaking, P problems are ones that can be solved rather fast - more exactly, their running time can be expressed as a polynom. NP problems on the other hand are problems where a simple method exists to verify if they are correct but it's still hard to solve them. To give a real-world example: If you have a number of objects and want to put them into a box. Though you don't know if they fit into the box. There's a vast number of possibilitys how to order the objects so they fit into the box, so it may be really hard to find out if it's possible at all. But if you have a solution (all objects are in the box), you can close the lit and easily see that the solution works (I'm not entirely sure on that but I think this is a variant of KNAPSACK). There's another important class of problems and that are NP complete problems. Those are like the "kings" of NP problems, their meaning is that if you have an efficient algorithm for one NP complete problem, you would be able to use that to solve all other NP problems.

NP problems are the basis of cryptography. The most popular public key algorithm, RSA, is based on the factoring problem. Factoring means that you divide a non-prime into a number of primes, for example factoring 6 results in 2*3. It is hard to do factoring on a large number, but if you have two factors, it's easy to check that they are indeed factors of the large number by multiplying them. One big problem with RSA (and pretty much all other cryptographic methods) is that it's possible that a trick exists that nobody has found yet which makes it easy to factorize a large number. Such a trick would undermine the basis of most cryptography used in the internet today, for example https/ssl.

What one would want to see is cryptography that is provable secure. This would mean that one can proove that it's really hard (where "really hard" could be something like "this is not possible with normal computers using the amount of mass in the earth in the lifetime of a human") to break it. With todays math, such proofs are nearly impossible. In math terms, this would be a lower bound for the complexity of a problem.

And that's where the P!=NP proof get's interesting. If it's true that P!=NP then this would mean NP problems are definitely more complex than P problems. So this might be the first breakthrough in defining lower bounds of complexity. I said above that I'm currently working on "proovable" security (with the example of RSA-PSS), but provable in this context means that you have core algorithms that you believe are secure and design your provable cryptographic system around it. Knowing that P!=NP could be the first step in having really "provable secure" algorithms at the heart of cryptography.

I want to stress that it's only a "first step". Up until today, nobody was able to design a useful public key cryptography system around an NP hard problem. Factoring is NP, but (at least as far as we know) it's not NP hard. I haven't covered the whole topic of quantum computers at all, which opens up a whole lot of other questions (for the curious, it's unknown if NP hard problems can be solved with quantum computers).

As a final conclusion, if the upper result is true, this will lead to a whole new aera of cryptographic research - and some of it will very likely end up in your webbrowser within some years.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Computer culture, Cryptography, English, Science

at

12:42

| Comments (2)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: cmi, cryptography, deolalikar, math, milleniumproblems, pnp, provablesecurity, security

Wednesday, June 4. 2008

Rapid Prototyping, 3D-Drucker, RepRap

Zum Thema Rapid Prototyping und dessen möglicherweise gravierenden gesellschaftlichen Auswirkungen las ich das erste mal in einen Text der Zukunftswerkstatt Jena, der im sehr lesenswerten Büchlein »Herrschaftsfrei Wirtschaften« veröffentlicht wurde (welches es auch komplett zum Download gibt).

Aber der Reihe nach: In der Debatte um freie Software, speziell in eher politisierten Kreisen (Stichworte sind hier etwa Ökonux oder das Keimform-Blog), wird des öfteren die Frage aufgeworfen, ob die Art und Weise, wie freie Software produziert wird, nicht als Modell für gesellschaftliches Wirtschaften insgesamt herhalten kann. Dabei wird oft der Begriff »Keimform« aus der Wertkritik gebraucht, der etwas bezeichnet, was zwar im bestehenden Kapitalismus und dessen Kontext stattfindet, aber erste Züge anderer Strukturen aufweist.

Nun stellt sich naiverweise erstmal die Herausforderung, dass immaterielle Güter (Software, Musik, Text) mit vernachlässigbarem Aufwand kopiert werden können, insofern die Adaption der Prinzipien freier Software hier nahe liegt (bestes Beispiel die Wikipedia), im Gegensatz dazu natürlich materielle Güter hier herausfallen, weil sie immer noch einen vergleichsweise großen Produktionsaufwand pro Stück besitzen.

Die Science-Fiction-lastig anmutende Frage »Lässt sich das ändern?« bringt uns nun zurück zum Thema Rapid Prototyping. Damit werden Verfahren bezeichnet, komplett automatisiert Gegenstände zu erschaffen, im einfachsten Beispiel etwa die (schon länger technisch machbaren) 3D-Drucker, die Kunststoffgebilde nach Computervorbild erschaffen können. Weiter gedacht könnten derartige Gerätschaften, wenn sie mit unterschiedlichen Materialien arbeiten, auch zur Produktion komplexerer Geräte genutzt werden.

Das Ziel, was sich vor einigen Jahren der Wissenschaftler Adrian Bowyer setzte, lautet nun: Eine Maschine, welche in der Lage ist, sich selbst neu zu erschaffen. Sozusagen vergleichbar mit dem Schritt, als der erste Compiler lernte, sich selbst zu übersetzen.

Heute vermeldet Golem, dass es erstmals gelungen ist, einen sogenannten RepRap dazu zu bringen, sich selbst zu reproduzieren. Von der Gesellschaft freier Güter mögen wir sicher noch ein Stück entfernt sein, sollte der RepRap allerdings tatsächlich das leisten, was seine Erfinder vermeldeten, sind wir ihr möglicherweise ein gutes Stück näher.

Achja: Der RepRap steht mit der GPL selbstverständlich unter einer freien Lizenz.

Aber der Reihe nach: In der Debatte um freie Software, speziell in eher politisierten Kreisen (Stichworte sind hier etwa Ökonux oder das Keimform-Blog), wird des öfteren die Frage aufgeworfen, ob die Art und Weise, wie freie Software produziert wird, nicht als Modell für gesellschaftliches Wirtschaften insgesamt herhalten kann. Dabei wird oft der Begriff »Keimform« aus der Wertkritik gebraucht, der etwas bezeichnet, was zwar im bestehenden Kapitalismus und dessen Kontext stattfindet, aber erste Züge anderer Strukturen aufweist.

Nun stellt sich naiverweise erstmal die Herausforderung, dass immaterielle Güter (Software, Musik, Text) mit vernachlässigbarem Aufwand kopiert werden können, insofern die Adaption der Prinzipien freier Software hier nahe liegt (bestes Beispiel die Wikipedia), im Gegensatz dazu natürlich materielle Güter hier herausfallen, weil sie immer noch einen vergleichsweise großen Produktionsaufwand pro Stück besitzen.

Die Science-Fiction-lastig anmutende Frage »Lässt sich das ändern?« bringt uns nun zurück zum Thema Rapid Prototyping. Damit werden Verfahren bezeichnet, komplett automatisiert Gegenstände zu erschaffen, im einfachsten Beispiel etwa die (schon länger technisch machbaren) 3D-Drucker, die Kunststoffgebilde nach Computervorbild erschaffen können. Weiter gedacht könnten derartige Gerätschaften, wenn sie mit unterschiedlichen Materialien arbeiten, auch zur Produktion komplexerer Geräte genutzt werden.

Das Ziel, was sich vor einigen Jahren der Wissenschaftler Adrian Bowyer setzte, lautet nun: Eine Maschine, welche in der Lage ist, sich selbst neu zu erschaffen. Sozusagen vergleichbar mit dem Schritt, als der erste Compiler lernte, sich selbst zu übersetzen.

Heute vermeldet Golem, dass es erstmals gelungen ist, einen sogenannten RepRap dazu zu bringen, sich selbst zu reproduzieren. Von der Gesellschaft freier Güter mögen wir sicher noch ein Stück entfernt sein, sollte der RepRap allerdings tatsächlich das leisten, was seine Erfinder vermeldeten, sind wir ihr möglicherweise ein gutes Stück näher.

Achja: Der RepRap steht mit der GPL selbstverständlich unter einer freien Lizenz.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Computer culture, Linux, Politics, Science

at

23:05

| Comments (0)

| Trackback (1)

Defined tags for this entry: 3ddrucker, freesoftware, freiegesellschaft, rapidprototyping, reprap, sciencefiction, society

Saturday, April 21. 2007

Tausche Seele gegen DVD

Die Webseite Blasphemy Challenge (via boingboing) bietet, im Tausch gegen die eigene Seele, eine DVD des religionskritischen Films »The God who wasn't there«.

Das ganze läuft folgendermaßen: In der Bibel, Markus 3, Vers 28 und 29, ist nachzulesen:

Amen, das sage ich euch: Alle Vergehen und Lästerungen werden den Menschen vergeben werden, so viel sie auch lästern mögen; wer aber den Heiligen Geist lästert, der hat keine Vergebung in Ewigkeit, sondern ist ewiger Sünde schuldig. (Übersetzung nach Luther, Copyright abgelaufen)

Sprich: Gott vergibt viel, eigentlich fast alles. Aber wer die Existenz des heiligen Geistes verneint, der macht sich der ewigen Sünde (ich finde ja da das Englische schicker, »eternal sin« klingt viel gewaltiger) schuldig. Zum Beweis der ewigen Sünde empfielt die Seite, ganz modern, ein youtube-Video, in dem der Satz »I deny the holy spirit« ausgesprochen wird.

Nunja, Seele gegen DVD, ein fairer Tausch wie ich finde, weswegen man mich hier bewundern kann. Ich hatte zuerst überlegt, noch ein paar schlaue Worte zu sagen, hab mich dann aber entschieden, dass das Videoblogging nicht so meine Welt ist, auf Englisch schon garnicht, und ich mich doch lieber auf's Schreiben verlege. Deswegen ist das Video auch komplett belanglos, bevor mir aber jemand vorwirft, proprietäre Formate zu befördern, gibt's das ganze natürlich wie üblich als ogg theora/vorbis.

Als nicht-US-Bürger muss man 8 Dollar für den Versand abdrücken. Rezension des Films gibt's dann natürlich hier sobald die DVD da ist.

Wenn also Gott existierte, gäbe es für ihn nur ein einziges Mittel, der menschlichen Freiheit zu dienen: aufhören zu existieren. (Michael Bakunin, Gott und der Staat)

Das ganze läuft folgendermaßen: In der Bibel, Markus 3, Vers 28 und 29, ist nachzulesen:

Amen, das sage ich euch: Alle Vergehen und Lästerungen werden den Menschen vergeben werden, so viel sie auch lästern mögen; wer aber den Heiligen Geist lästert, der hat keine Vergebung in Ewigkeit, sondern ist ewiger Sünde schuldig. (Übersetzung nach Luther, Copyright abgelaufen)

Sprich: Gott vergibt viel, eigentlich fast alles. Aber wer die Existenz des heiligen Geistes verneint, der macht sich der ewigen Sünde (ich finde ja da das Englische schicker, »eternal sin« klingt viel gewaltiger) schuldig. Zum Beweis der ewigen Sünde empfielt die Seite, ganz modern, ein youtube-Video, in dem der Satz »I deny the holy spirit« ausgesprochen wird.

Nunja, Seele gegen DVD, ein fairer Tausch wie ich finde, weswegen man mich hier bewundern kann. Ich hatte zuerst überlegt, noch ein paar schlaue Worte zu sagen, hab mich dann aber entschieden, dass das Videoblogging nicht so meine Welt ist, auf Englisch schon garnicht, und ich mich doch lieber auf's Schreiben verlege. Deswegen ist das Video auch komplett belanglos, bevor mir aber jemand vorwirft, proprietäre Formate zu befördern, gibt's das ganze natürlich wie üblich als ogg theora/vorbis.

Als nicht-US-Bürger muss man 8 Dollar für den Versand abdrücken. Rezension des Films gibt's dann natürlich hier sobald die DVD da ist.

Wenn also Gott existierte, gäbe es für ihn nur ein einziges Mittel, der menschlichen Freiheit zu dienen: aufhören zu existieren. (Michael Bakunin, Gott und der Staat)

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Life, Movies, Politics, Science

at

12:04

| Comments (2)

| Trackback (1)

Defined tags for this entry: blashpemy, blasphemychallenge, gott, heiligergeist, holyspirit, religion, seele, sin, sünde

Monday, March 12. 2007

Automobil

Ich gehör ja noch zu den Idealisten, die wegen Klimawandel, Lärm, Waldsterben, Fächenverbrauch und Co. kein Auto besitzen. Allerdings weiss ich gelegentlich die Nutzung eines fahrbaren Untersatzes doch zu schätzen, finde jedoch bei dem, was es gerade auf dem Markt gibt, nichts, was ansatzweise akzeptabel wär. Zwar hege ich keine seltsam nationalistischen Vorurteile gegen Toyota, finde den Verbrauch des Autos von Boris Palmer jedoch mit knapp 5 Litern immer noch weit über dem, was man eigentlich will. Kleiner 2l/100km wär schon Requirement.

Stefan bloggt über den Loremo, was schonmal deutlich besser klingt. Zwar Diesel (Rußpartikel, Feinstaub), aber immerhin mal ein Spritverbrauch, der für die nächsten 10 Jahre noch im akzeptablen Bereich liegt.

Stefan bloggt über den Loremo, was schonmal deutlich besser klingt. Zwar Diesel (Rußpartikel, Feinstaub), aber immerhin mal ein Spritverbrauch, der für die nächsten 10 Jahre noch im akzeptablen Bereich liegt.

Thursday, December 28. 2006

23C3 - report first day

Still here at the 23C3, I'll try to summarize some things about the talks I've visited yesterday.

First was a presentation about the Trust model of GPG/PGP and an alternative approach. I wasn't so impressed, because I think the main lack from the web-of-trust-infrastructure is that it's too complex to understand for the masses.

The Lightning-Talks were quite nice, some guy presented some live-hacks to a poorly designed travel agency, which was very funny. I personally presented compiz and told some short things about the situation of 3D-graphics and desktops.

I saw about the last 10 minutes of a talk about Drones, camera-supplied small devices flying around, and thoughts what these devices could mean for the society. A group is working on creating such devices on quite small costs. I'll have to fully view that on video after the congress.

Another very interesting Talk: »The gift of sharing«, the referent presented thoughts what kind of »economy-structure« the free software development should be called. It was a bit difficult to follow the talk, as it was in english and I'm no native english speaker. There's a paper from the guy which is probably worth reading.

The last talk was about wiki knowledge and citing that in science. The referents plan to create an RFC for citing-URLs in Wikis.

What irritated me was a computer science professor telling that she wouldn't allow her students to cite wikis, with the stupid argument they should cite their sources from books, completely igonring that science can happen in wikis and it may be the original source of the knowledge, not just something that has been explored elsewhere. Ruediger Weiss gave good arguments against that and mentioned that he thinks wiki is really a new kind of doing science and should be handled as such.

To be continued.

First was a presentation about the Trust model of GPG/PGP and an alternative approach. I wasn't so impressed, because I think the main lack from the web-of-trust-infrastructure is that it's too complex to understand for the masses.

The Lightning-Talks were quite nice, some guy presented some live-hacks to a poorly designed travel agency, which was very funny. I personally presented compiz and told some short things about the situation of 3D-graphics and desktops.

I saw about the last 10 minutes of a talk about Drones, camera-supplied small devices flying around, and thoughts what these devices could mean for the society. A group is working on creating such devices on quite small costs. I'll have to fully view that on video after the congress.

Another very interesting Talk: »The gift of sharing«, the referent presented thoughts what kind of »economy-structure« the free software development should be called. It was a bit difficult to follow the talk, as it was in english and I'm no native english speaker. There's a paper from the guy which is probably worth reading.

The last talk was about wiki knowledge and citing that in science. The referents plan to create an RFC for citing-URLs in Wikis.

What irritated me was a computer science professor telling that she wouldn't allow her students to cite wikis, with the stupid argument they should cite their sources from books, completely igonring that science can happen in wikis and it may be the original source of the knowledge, not just something that has been explored elsewhere. Ruediger Weiss gave good arguments against that and mentioned that he thinks wiki is really a new kind of doing science and should be handled as such.

To be continued.

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Computer culture, English, Gentoo, Linux, Politics, Science

at

16:41

| Comments (0)

| Trackbacks (0)

Tuesday, October 17. 2006

Enigma

Unter dem Titel »Hieroglyphen, Enigma, RSA - Eine Geschichte der Kryptographie« fanden heute an der Uni Karlsruhe zwei Vorträge, sowie eine anschließende Besichtigung der Sammlung von Klaus Kopacz.

Unter dem Titel »Hieroglyphen, Enigma, RSA - Eine Geschichte der Kryptographie« fanden heute an der Uni Karlsruhe zwei Vorträge, sowie eine anschließende Besichtigung der Sammlung von Klaus Kopacz.Ich hatte zum ersten mal die Gelegenheit, originale Enigma-Maschinen zu sehen und bekam auch im Vortrag einen Eindruck, wie überhaupt genau der Verschlüsselungsalgorithmus der Enigma funktionierte.

Enigma-Bilder gibt's hier

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Computer culture, Cryptography, Life, Science

at

20:01

| Comment (1)

| Trackbacks (0)

Defined tags for this entry: cryptography, enigma

Friday, September 22. 2006

Verschwörungstheoretiker und Sektenanhänger in der Jugendumweltbewegung

Nachfolgender Artikel liegt schon viel zu lang unveröffentlicht auf meiner Platte. Wird warscheinlich im nächsten Grünen Blatt erscheinen und darf gern auch anderswo veröffetnlicht werden (officetaugliches Format auf Anfrage).

Continue reading "Verschwörungstheoretiker und Sektenanhänger in der Jugendumweltbewegung"

Posted by Hanno Böck

in Ecology, Politics, Science

at

23:24

| Comments (7)

| Trackback (1)

Defined tags for this entry: esoterik, jugendumweltbewegung, jukss, ngm, scientology, sekten, universellesleben, vogelgrippe

(Page 1 of 2, totaling 26 entries)

» next page