Wednesday, April 19. 2017

Passwords in the Bug Reports (Owncloud/Nextcloud)

A while ago I wanted to report a bug in one of Nextcloud's apps. They use the Github issue tracker, after creating a new issue I was welcomed with a long list of things they wanted to know about my installation. I filled the info to the best of my knowledge, until I was asked for this:

A while ago I wanted to report a bug in one of Nextcloud's apps. They use the Github issue tracker, after creating a new issue I was welcomed with a long list of things they wanted to know about my installation. I filled the info to the best of my knowledge, until I was asked for this:The content of config/config.php:

Which made me stop and wonder: The config file probably contains sensitive information like passwords. I quickly checked, and yes it does. It depends on the configuration of your Nextcloud installation, but in many cases the configuration contains variables for the database password (dbpassword), the smtp mail server password (mail_smtppassword) or both. Combined with other information from the config file (e. g. it also contains the smtp hostname) this could be very valuable information for an attacker.

A few lines later the bug reporting template has a warning (“Without the database password, passwordsalt and secret”), though this is incomplete, as it doesn't mention the smtp password. It also provides an alternative way of getting the content of the config file via the command line.

However... you know, this is the Internet. People don't read the fineprint. If you ask them to paste the content of their config file they might just do it.

User's passwords publicly accessible

The issues on github are all public and the URLs are of a very simple form and numbered (e. g. https://github.com/nextcloud/calendar/issues/[number]), so downloading all issues from a project is trivial. Thus with a quick check I could confirm that some users indeed posted real looking passwords to the bug tracker.

Nextcoud is a fork of Owncloud, so I checked that as well. The bug reporting template contained exactly the same words, probably Nextcloud just copied it over when they forked. So I reported the issue to both Owncloud and Nextcloud via their HackerOne bug bounty programs. That was in January.

I proposed that both projects should go through their past bug reports and remove everything that looks like a password or another sensitive value. I also said that I think asking for the content of the configuration file is inherently dangerous and should be avoided. To allow users to share configuration options in a safe way I proposed to offer an option similar to the command line tool (which may not be available or usable for all users) in the web interface.

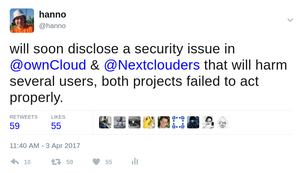

The reaction wasn't overwhelming. Apart from confirming that both projects acknowledged the problem nothing happened for quite a while. During FOSDEM I reached out to members of both projects and discussed the issue in person. Shortly after that I announced that I intended to disclose this issue three months after the initial report.

Disclosure deadline was nearing with passwords still public

The deadline was nearing and I didn't receive any report on any actions being taken by Owncloud or Nextcloud. I sent out this tweet which received quite some attention (and I'm sorry that some people got worried about a vulnerability in Owncloud/Nextcloud itself, I got a couple of questions):

In all fairness to NextCloud, they had actually started scrubbing data from the existing bug reports, they just hadn't informed me. After the tweet Nextcloud gave me an update and Owncloud asked for a one week extension of the disclosure deadline which I agreed to.

The outcome by now isn't ideal. Both projects have scrubbed all obvious passwords from existing bug reports, although I still find values where it's not entirely clear whether they are replacement values or just very bad passwords (e. g. things like “123456”, but you might argue that people using such passwords have other problems).

Nextcloud has changed the wording of the bug reporting template. The new template still asks for the config file, but it mentions the safer command line option first and has the warning closer to the mentioning of the config. This is still far from ideal and I wouldn't be surprised if people continue pasting their passwords. However Nextcloud developers have indicated in the HackerOne discussion that they might pick up my idea of offering a GUI version to export a scrubbed config file. Owncloud has changed nothing yet.

If you have reported bugs to Owncloud or Nextcloud in the past and are unsure whether you may have pasted your password it's probably best to change it. Even if it's been removed now it may still be available within search engine caches or it might have already been recorded by an attacker.

Saturday, April 8. 2017

And then I saw the Password in the Stack Trace

I want to tell a little story here. I am usually relatively savvy in IT security issues. Yet I was made aware of a quite severe mistake today that caused a security issue in my web page. I want to learn from mistakes, but maybe also others can learn something as well.

I have a private web page. Its primary purpose is to provide a list of links to articles I wrote elsewhere. It's probably not a high value target, but well, being an IT security person I wanted to get security right.

Of course the page uses TLS-encryption via HTTPS. It also uses HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS), TLS 1.2 with an AEAD and forward secrecy, has a CAA record and even HPKP (although I tend to tell people that they shouldn't use HPKP, because it's too easy to get wrong). Obviously it has an A+ rating on SSL Labs.

Surely I thought about Cross Site Scripting (XSS). While an XSS on the page wouldn't be very interesting - it doesn't have any kind of login or backend and doesn't use cookies - and also quite unlikely – no user supplied input – I've done everything to prevent XSS. I set a strict Content Security Policy header and other security headers. I have an A-rating on securityheaders.io (no A+, because after several HPKP missteps I decided to use a short timeout).

I also thought about SQL injection. While an SQL injection would be quite unlikely – you remember, no user supplied input – I'm using prepared statements, so SQL injections should be practically impossible.

All in all I felt that I have a pretty secure web page. So what could possibly go wrong?

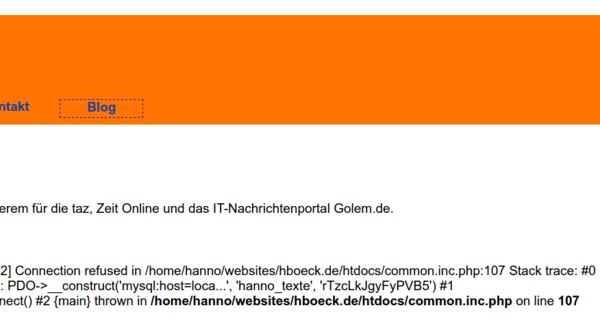

Well, this morning someone send me this screenshot:

And before you ask: Yes, this was the real database password. (I changed it now.)

So what happened? The mysql server was down for a moment. It had crashed for reasons unrelated to this web page. I had already taken care of that and hadn't noted the password leak. The crashed mysql server subsequently let to an error message by PDO (PDO stands for PHP Database Object and is the modern way of doing database operations in PHP).

The PDO error message contains a stack trace of the function call including function parameters. And this led to the password leak: The password is passed to the PDO constructor as a parameter.

There are a few things to note here. First of all for this to happen the PHP option display_errors needs to be enabled. It is recommended to disable this option in production systems, however it is enabled by default. (Interesting enough the PHP documentation about display_errors doesn't even tell you what the default is.)

display_errors wasn't enabled by accident. It was actually disabled in the past. I made a conscious decision to enable it. Back when we had display_errors disabled on the server I once tested a new PHP version where our custom config wasn't enabled yet. I noticed several bugs in PHP pages. So my rationale was that disabling display_errors hides bugs, thus I'd better enable it. In hindsight it was a bad idea. But well... hindsight is 20/20.

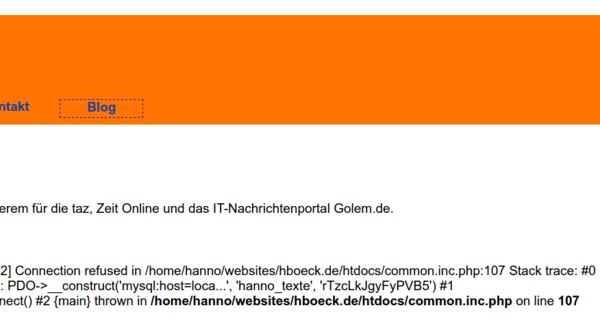

The second thing to note is that this only happens because PDO throws an exception that is unhandled. To be fair, the PDO documentation mentions this risk. Other kinds of PHP bugs don't show stack traces. If I had used mysqli – the second supported API to access MySQL databases in PHP – the error message would've looked like this:

While this still leaks the username, it's much less dangerous. This is a subtlety that is far from obvious. PHP functions have different modes of error reporting. Object oriented functions – like PDO – throw exceptions. Unhandled exceptions will lead to stack traces. Other functions will just report error messages without stack traces.

If you wonder about the impact: It's probably minor. People could've seen the password, but I haven't noticed any changes in the database. I obviously changed it immediately after being notified. I'm pretty certain that there is no way that a database compromise could be used to execute code within the web page code. It's far too simple for that.

Of course there are a number of ways this could've been prevented, and I've implemented several of them. I'm now properly handling exceptions from PDO. I also set a general exception handler that will inform me (and not the web page visitor) if any other unhandled exceptions occur. And finally I've changed the server's default to display_errors being disabled.

While I don't want to shift too much blame here, I think PHP is making this far too easy to happen. There exists a bug report about the leaking of passwords in stack traces from 2014, but nothing happened. I think there are a variety of unfortunate decisions made by PHP. If display_errors is dangerous and discouraged for production systems then it shouldn't be enabled by default.

PHP could avoid sending stack traces by default and make this a separate option from display_errors. It could also introduce a way to make exceptions fatal for functions so that calling those functions is prevented outside of a try/catch block that handles them. (However that obviously would introduce compatibility problems with existing applications, as Craig Young pointed out to me.)

So finally maybe a couple of takeaways:

I have a private web page. Its primary purpose is to provide a list of links to articles I wrote elsewhere. It's probably not a high value target, but well, being an IT security person I wanted to get security right.

Of course the page uses TLS-encryption via HTTPS. It also uses HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS), TLS 1.2 with an AEAD and forward secrecy, has a CAA record and even HPKP (although I tend to tell people that they shouldn't use HPKP, because it's too easy to get wrong). Obviously it has an A+ rating on SSL Labs.

Surely I thought about Cross Site Scripting (XSS). While an XSS on the page wouldn't be very interesting - it doesn't have any kind of login or backend and doesn't use cookies - and also quite unlikely – no user supplied input – I've done everything to prevent XSS. I set a strict Content Security Policy header and other security headers. I have an A-rating on securityheaders.io (no A+, because after several HPKP missteps I decided to use a short timeout).

I also thought about SQL injection. While an SQL injection would be quite unlikely – you remember, no user supplied input – I'm using prepared statements, so SQL injections should be practically impossible.

All in all I felt that I have a pretty secure web page. So what could possibly go wrong?

Well, this morning someone send me this screenshot:

And before you ask: Yes, this was the real database password. (I changed it now.)

So what happened? The mysql server was down for a moment. It had crashed for reasons unrelated to this web page. I had already taken care of that and hadn't noted the password leak. The crashed mysql server subsequently let to an error message by PDO (PDO stands for PHP Database Object and is the modern way of doing database operations in PHP).

The PDO error message contains a stack trace of the function call including function parameters. And this led to the password leak: The password is passed to the PDO constructor as a parameter.

There are a few things to note here. First of all for this to happen the PHP option display_errors needs to be enabled. It is recommended to disable this option in production systems, however it is enabled by default. (Interesting enough the PHP documentation about display_errors doesn't even tell you what the default is.)

display_errors wasn't enabled by accident. It was actually disabled in the past. I made a conscious decision to enable it. Back when we had display_errors disabled on the server I once tested a new PHP version where our custom config wasn't enabled yet. I noticed several bugs in PHP pages. So my rationale was that disabling display_errors hides bugs, thus I'd better enable it. In hindsight it was a bad idea. But well... hindsight is 20/20.

The second thing to note is that this only happens because PDO throws an exception that is unhandled. To be fair, the PDO documentation mentions this risk. Other kinds of PHP bugs don't show stack traces. If I had used mysqli – the second supported API to access MySQL databases in PHP – the error message would've looked like this:

PHP Warning: mysqli::__construct(): (HY000/1045): Access denied for user 'test'@'localhost' (using password: YES) in /home/[...]/mysqli.php on line 3While this still leaks the username, it's much less dangerous. This is a subtlety that is far from obvious. PHP functions have different modes of error reporting. Object oriented functions – like PDO – throw exceptions. Unhandled exceptions will lead to stack traces. Other functions will just report error messages without stack traces.

If you wonder about the impact: It's probably minor. People could've seen the password, but I haven't noticed any changes in the database. I obviously changed it immediately after being notified. I'm pretty certain that there is no way that a database compromise could be used to execute code within the web page code. It's far too simple for that.

Of course there are a number of ways this could've been prevented, and I've implemented several of them. I'm now properly handling exceptions from PDO. I also set a general exception handler that will inform me (and not the web page visitor) if any other unhandled exceptions occur. And finally I've changed the server's default to display_errors being disabled.

While I don't want to shift too much blame here, I think PHP is making this far too easy to happen. There exists a bug report about the leaking of passwords in stack traces from 2014, but nothing happened. I think there are a variety of unfortunate decisions made by PHP. If display_errors is dangerous and discouraged for production systems then it shouldn't be enabled by default.

PHP could avoid sending stack traces by default and make this a separate option from display_errors. It could also introduce a way to make exceptions fatal for functions so that calling those functions is prevented outside of a try/catch block that handles them. (However that obviously would introduce compatibility problems with existing applications, as Craig Young pointed out to me.)

So finally maybe a couple of takeaways:

- display_errors is far more dangerous than I was aware of.

- Unhandled exceptions introduce unexpected risks that I wasn't aware of.

- In the past I was recommending that people should use PDO with prepared statements if they use MySQL with PHP. I wonder if I should reconsider that, given the circumstances mysqli seems safer (it also supports prepared statements).

- I'm not sure if there's a general takeaway, but at least for me it was quite surprising that I could have such a severe security failure in a project and code base where I thought I had everything covered.

(Page 1 of 1, totaling 2 entries)